|

|

A previous entry described how to plan using cost and business value estimates. It’s really very simple:

- The customer chooses stories and the order in which to implement them, the most valuable first, the stories with the best value/cost ratio first, the stories with the most demo potential first…

- We implement the stories one by one, in the order specified by the customer

- If we don’t have enough time at the end of the release, some low-value story might not get implemented

- If we have some time left, the customer chooses another story, from the list of “if we have time” stories.

Is the real world that simple? Of course not. You have to take into account risk.

Some of the stories are riskier than others. What could the risk be ?

- The story implementation requires some new tools, a new package, a new algorithm. Anything new is always risky (or as Jerry Weinberg says “Nothing new ever works“).

- Implementation requires coordination and cooperation with another team, another division, another company. The further away, the riskier.

- The functionality affects many parts of the application.

- Your risk here

For example, in the current release there are two risky stories: one is the redefinition of an existing product, the second one is the definition of a new product. Why are these two stories risky?

- The redefinition of the first product will allow us to simplify product handling. This refactoring will touch most of the modules in the application. We will have to migrate existing data. The result has to be completely transparent and compatible with the previous release.

- The definition of the new product is a trial for a new way of structuring products. If it works out, we will (re)structure all of our products this way. If it doesn’t work…

- These products have to be defined by another team. We specify the changes, they implement them and (after a while) we get back a file containing updated product definitions.

How do we deal with this?

- Risky stories get a higher priority. We schedule these stories early in the release. The product re-definition was the first story of the release. Coordination with the product defining team started before this release, so that the new definition would be ready at the start of the release. And lucky we did it this way: due to a misunderstanding, the product re-definition was only half complete. And the person responsible for these product definitions went away on holiday. Because this risk materialized early in the release we didn’t panic, we have some time left to correct the situation.

- We have a fallback plan. Plan B.. What do we do if the worst comes to the worst and the story fails completely? In both cases, the fallback is to continue to use the current products. These products are not as effective to work with, both for IT and users, but we can get the job done.

So, the normal case is very simple: implement stories in business value order. But for some risky stories you also:

- Identify the risks, their severity and their likelyhood. Focus on those that are severe and likely

- Find ways to avoid the risk or to deal with the materialization of the risk

- Schedule the risky stories earlier in the release, so that you have the time to deal with the risk.

You’ve got stories. Each story has a cost and value. You”re working on the release.

How do you know if you’re on track? How do you let everyone know where you are?

You use a Burn up/down chart.

This chart shows the state of the release I’m currently working on. This chart hangs on the wall where everyone can see it, as an “information radiator”. People from other teams wander over and come look at it (*).

This release will take 10 weeks, we just finished our second week. Each week we add another red and green sticker (we should use bigger stickers):

- red = % work left to do = the sum of the cost of all finished stories / the sum of the cost of all planned stories

- green = % of value implemented = the sum of the value of all finished stories / the sum of the value of all planned stories

I’ve got a very simple Excel sheet set up to calculate these percentages, but it wouldn’t be hard to do these calculations by hand.

What would a ‘healthy‘ burn up/down chart look like? I would expect

- The cost line to go down evenly, within a few % tolerance of a straight line from 100% to 0% TODO

- The value line to go up a bit more steeply than a straight line during the first half of the project; to be less steep during the second half. This is because we work on the high value stories first, as the customer planned them.

If all goes well, we end up at a bit less than 0% TODO and a bit more than 100% value at the end of the project, because we’ve done a bit more than expected, given the previous release’s velocity. If this happens, we will start the next release with a higher velocity; we will be able to take on some more work.

In our planning game we actually select two sets of stories:

- The stories, ordered by the customer, that we commit to, given our cost estimates and velocity

- Some stories that we’ll implement “if we have some time left“. If we work faster than expected or if the customer drops one of the stories from the plan (as happened the previous release), we have a small set of stories ready to be added to the release. We can re-plan quickly by holding an extra planning game.

(*) One project manager looked at the chart and asked a few questions about it. I explained this showed our team’s progress over the 10-week project. His reponse: “Yeah, you can do this sort of stuff because you do small, manageable projects. I do large, unmanageable projects. And I feel we’re not making progress“. What? With all the time spent on putting data into Microsoft Project and massaging those numbers, you don’t know how your project is doing?

Theory of Constraints session at XP2005, participants were given an experiential crash course in the Theory of Constraints. They then had to apply their new knowledge to solve real world problems.

They did this in 3 groups. Each group had a “customer”, the others played “TOC consultant” to help the customer to understand and improve their system.

|

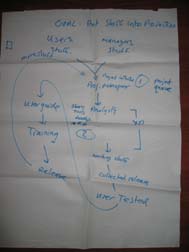

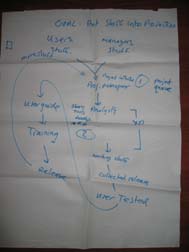

This is the output of one of the groups: it gives an overview of the whole process from requirements, over analysis, development, testing, writing manuals, training and finally putting “stuff” into production.

Click to enlarge the image

(picture courtesy of Marc Evers) |

Remarks about the poster

The goal of the system is to “Put stuff into production“. An IT system can only generate value when it’s put into production use and users are actually using it (well). Hence the User Guide and training before releasing. Part of the value in releasing a system is the feedback and ideas you receive to improve the system, hence the loop back to project initiation.

The bottleneck of this system was actually two bottlenecks (indicated as [1] and [2]), which ocurred at different times during the project. Bottleneck [1] holds the system back at the beginning of the project; bottleneck[2] holds the system back near the end of the project. It’s not as bad as a “constantly shifting constraint”, but we need to focus in different areas depending on the phase of the project.

Notice how the part marked with “XP” is between two bottlenecks. This is something that has been observed in many (if not most) XP projects: XP has very effective techniques to exploit, subordinate to and elevate a development team bottleneck. If you apply the techniques, the development team’s throughput improves a lot and it’s no longer the bottleneck. The bottleneck shifts. And who’s the bottleneck then? Usually the Customer (role) becomes the bottleneck, either in keeping the team fed with stories or in accepting the stream of finished features. Or both, as in this case.

XP in a nutshell, from a Theory of Constraints perspective:

- XP assumes that the development team is the bottleneck

- IF this is correct, XP increases the throughput of the development team and thereby shifts the bottleneck to the Customer

- If this assumption is not correct…

In the session we chose one bottleneck to concentrate on, the one the customer wanted to remove the most.

Our newly graduated “TOC consultants” suggested several ways to exploit, subordinate and elevate these bottlenecks, coming up with some novel ideas that their customer could apply to this situation. What are some of the interventions we could suggest here?

- We have two bottlenecks, before and after “XP”. They are bottlenecks at different times in the project. If they are different resources, they could help each other out: bottleneck [2] resources can help (subordinate to) bottleneck [1] resources at the beginning of the project; and vice-versa at the end of the project. E.g. testers can help analysts at the start of the project by devising acceptance tests; analysts can help testers to perform and analyze acceptance tests.

- We have a non-bottleneck resource, the “XP” team. They could subordinate to both bottlenecks, by spending some of their slack time in helping the bottlenecks. One way of doing is to assign one person from the development team to “follow the release”. This developer helps the analysts to write stories and clarify acceptance tests. They also help the testers during acceptance, the writers writing manuals, the operators installing the software. Their primary job is to smooth the interface between the development team and the world outside the team. They have a good overview of both the functional and technical content of the release. While this developer works at the end of the release, another developer starts preparing the next release and follows that release through to the end. This is a “rolling wave” planning, which is great for continuity and is a good way of “leveling the load” (One of the 14 principles of the Toyota Way). You do need people in the development team who are skilled at interfacing with other teams, who understand both the functional and technical side of a project…

This previous blog entry exhorted you to go out and talk to your friendly neighbourhood business person.

What will you talk about? A good place to start is to discuss the cost and value of what you’re doing. One of the most powerful tools of XP is “The Planning Game”. You sit down with your customer(s) and decide which features you’re going to implement in the next release. To do this you need:

- Index cards with a “story” each. The card contains a brief description of a feature, just enough to remind developers and customers of the important points of the feature, which they have discussed before and both understand.

- Each card contains an estimate of the required effort to implement the story. Different teams use different units for their estimates: mandays, hours, “ideal days”, gummibears… I just use a scale from 1-6 “story points“

The index cards are easy to lay out on a big table, you get an good overview, it’s easy to move them around. The aim of the game is to define an implementation plan that will generate the highest possible value with the least cost. How do we do this? We already know the cost (albeit in “points”. What’s that in the “real world”?). What is the value of a story? Well, that’s a question for the business people to answer.

Business people have to estimate the potential business value they can gain by putting this story into production use. How do they do that? I use a very simple process, the same one I use to estimate the cost of the story:

- Sort all stories from low to high value, by taking them one by one and comparing them with the stories that have already been sorted.

- When all stories have been sorted, check if the ordering seems correct.

- Give the lowest value story 1 point. Give the highest value story 5-6 points (or whatever maximum you set on value estimations). Don’t use a range that’s too big:

- It might give an impression of precision where there is none

- If some stories are really worth 100 times more than others, why are you wasting time on those stories with ludicrously low value?

- Group the remaining stories in groups with roughly equal value and give them values between 1 and 5. Each story now has an estimated “business value point“.

- Done!

And now planning becomes very easy… Just pick the stories with a good value/cost ratio.

How long does that take? I just did one for a 2-month release with 4 developers and about 30 stories. Estimating costs took two sessions of almost an hour. Estimating value and planning the release took a little over an hour. Let’s say 3-4 hours to estimate and plan a 2-month release. YMMV.

It doesn’t cost a lot of effort to estimate your stories’ business value, but it has some interesting advantages:

- Planning becomes a lot easier

- It makes everybody think hard about the value of each story.

- Some features turn out of to have little or no value. Why should we waste our precious time on them?

- Some features turn out to have a lot more value than technical people would expect.

- Tracking value sends a powerful positive message: we are adding value to the organisation. IT is not a bottomless pit where you pour resources in. IT is a system that generates value for a given investment.

- It clearly delineates the responsibilities of developers and business people

- The developers are responsible for keeping the cost of the stories low

- The business people are responsible for finding and selecting high value stories

- You will know it’s time to stop the project when the added value of the next release is low.

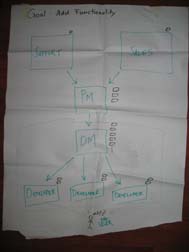

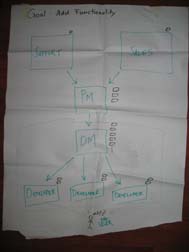

This is the output of the second group. The “bottleneck” of this system is easy to spot: everything has to go through 2 people. The stacks of work in front of each person indicates how much work in progress accumulates in front of each resource. This is the output of the second group. The “bottleneck” of this system is easy to spot: everything has to go through 2 people. The stacks of work in front of each person indicates how much work in progress accumulates in front of each resource.

Click to enlarge the image

(picture courtesy of Marc Evers)

Some remarks

The goal of the system is to “add functionality” to an existing system. This functionality creates value only when it’s delivered to the customer. But that seems to take an inordinately long time, as the snoozing customer would indicate.

The bottleneck is the Development Manager (DM), with the Project Manager (PM) as bottleneck-in-waiting. All the work has to go through these two people. In the case of the Development Manager, all work goes through them several times: the DM carefully prepares and assigns the work to the developers, helps them design and develop and then the work has to come back for review(s).

How can we improve this situation?

- Currently, the PM explains the required functionalities to the DM. The DM then explains the functionalities to the developers. We could exploit the DM by having the PM explain the functionalities to the DM and developers at the same time. This could help break the “barrier” which now exists between business and development.

- If a few developers have more experience, they could subordinate to the DM by helping other developers and reviewing their code.

- We could elevate the constraint by hiring someone else to take on some of the duties of the DM or by training the most experienced developer(s) to take on some of the DM work.

However, these interventions might not be easy. It’s a stressful, difficult job, being the bottleneck. But it also make one very important. Having to delegate some of the work might be seen as “not being up to my job” or reduce the bottleneck’s importance.

The “barrier” in the system could be caused by the DM wanting to “shield” the team from the rest of the organisation. This way, the DM controls everything that goes in and out of the team. Some of the TOC interventions might reduce the amount of control the DM has. This too might be a touchy subject.

I do have a question about this diagram. How does the software get from the developers to the end user? We saw that the code goes back to the DM, for review. What happens next? Is there a Q/A procedure? Does the software get packaged, distributed or installed?

|