Decisions by consensus

One of the Toyota Way principles is « Nemawashi », take decisions by consensus.

Building consensus is a slow process, but it’s necessary to get everybody on board before taking a decision. Otherwise, the implementation will be delayed and (unconsciously) sabotaged by those who didn’t agree or weren’t involved.

It’s not just about building support for your ideas. The consensus-building process solicits ideas and review from everyone involved so that the final idea is usually a lot stronger than the original.

But there’s one big misunderstanding about consensus.

Consensus doesn’t require Compromise

It’s tempting to dilute our idea to reach consensus, ensure that everyone gets a bit of what they want, so that they’ll agree to go along.

It’s tempting to dilute our idea to reach consensus, ensure that everyone gets a bit of what they want, so that they’ll agree to go along.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In “Extreme Toyota” the authors show how Toyota embraces conflicts and doesn’t settle for compromises. They identify six contradictions that are central to Toyota’s way of working:

- Moving gradually and taking big leaps

- Cultivating frugality while spending huge sums

- Operating efficiently as well as redundantly

- Cultivating stability and a paranoid mindset

- Respecting bureaucratic hierarchy and allowing freedom to dissent

- Maintaining simplified and complex communication

“This AND that” sounds better than “This OVER that”… I want to have my cake and eat it too 😉

Enter the business consultants

A few years ago I worked on a project that automated the whole value stream of a business unit. The main challenge was that the different departments had conflicting needs. No surprise there.

One of the conflicts was between the production department that did the work on customer demand and the sales department that sold contracts for doing the work to the customer . The production department needed standardised products with little variation so that they could work efficiently, predictably and hit their Service Level Agreements; the sales team needed customised products so that they could tailor their offering precisely to what the customer needed.

This is a classical conflict. The business consultants on the project called this “Operational Excellence” versus “Customer Intimacy“. And the consultants said we had to choose. It’s one or the other, you can’t have both. It’s like Henry Ford’s saying: “You can have any color car, as long as that color is black.”

Examining the conflict

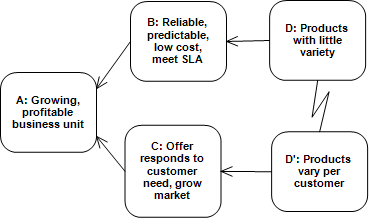

It’s clear, you can’t have both standardised and customised at the same time. There’s a clear conflict. But we have a tool to deal with conflicts: the Conflict Resolution Diagram. Let’s apply the tool:

- To have a growing, profitable business unit (A) we need to sell what the customer needs (C) and deliver it reliably and cheaply (B).

- To produce reliably, predictably at low cost and to hit the Service Level Agreements (B) we need products with little variety (D).

- To create an offer that responds to the customer’s need and to grow our market (C) we need to vary our products per customer (D’).

- Conflict: we can’t have little variation (D) and a lot of variation (D’) at the same time, but we need both.

Questioning assumptions

We deal with the conflict by questioning the underlying assumptions. Can we find fault with our logic? Bill Dettmer recommends to restate the relationships in “extreme wording”. For example:

- There’s absolutely no way to have both low and high variability at the same time! Well, duh!

- The only way to be profitable and reliable is to have low variability! Well, it was hard to fault this reasoning as this company operated on large volumes with low margins and tight competition.

- Customers always need special cases! Not always, but customers were no longer satisfied with one-size-fits-all offers. If this company couldn’t offer customised products, the competitors would be more than willing to get a new customer.

- We could have low variability and yet vary per customer if only we didn’t have so many customers! Going niche wasn’t an option for economical and legal reasons.

We looked at it every way possible and couldn’t find a fault with the reasoning until…

Finally, some clarity

The Logical Thinking Processes have a set of “Legitimate Reservations”, a set of critical questions we should ask. The first one is simply called “Clarity“: is the meaning of every word and sentence clear to everybody?

Now, we had already noticed that the different departments seemed to have different definitions for the same word. There were even differences in the way they described the different products to us. Were we talking about the same thing?

The breakthrough came when we asked “What do you mean by ‘Product’?” A product for the Production department wasn’t the same thing as a product for the Sales department. And the accounting & finance department had another definition of product. But… That’s not a bug; it’s a feature: if a Production-Product is different from a Sales-Product, can we have Production-Products with low variation and Sales-Products with high variation?

After a lot more work we came up with a way to standardise Production-Products on a small set of “building blocks” and let Sales create Sales-Products by mixing and matching the building blocks according to customer need. Then we mapped Production-Products onto Accounting-Products. And everybody got what they wanted: Operational Excellence AND Customer Intimacy.

Embrace conflict

We didn’t settle for a compromise, but spent the time to really think through our conflicts and come up with a solution that satisfied all needs. A conflict can be an opportunity to come up with an innovative solution.

You don’t have to settle for compromises if you think about it.

Picture of Bonsai by A. Marques. Thank you.