|

|

Into the heart of darkness. And back again.

I just don’t seem to learn, do I?

Don’t touch anything!

The previous story told how I did one last project before I left this company. This project involved customisation (for one customer) of the way data was acquired and processed by two applications. In the past, when I changed these applications, I would always introduce errors. My project manager’s motto was “If it works, don’t touch it!”. As if this application was a house of cards… Unfortunately most of the code didn’t work. I had to change some critical code to implement this customisation.

There be monsters here!

Why did I get this project? Probably because no one else dared to take on this project. The main part of the coding would be deep in the bowels of the applications, written long ago. It was like a dark, dank, dangerous dungeon nobody dared to enter. There had been some stories about people going in, but they hadn’t been seen again. Why did I get this project? Probably because no one else dared to take on this project. The main part of the coding would be deep in the bowels of the applications, written long ago. It was like a dark, dank, dangerous dungeon nobody dared to enter. There had been some stories about people going in, but they hadn’t been seen again.

Test yourself!

This feature was intended for one customer. The number one requirement was that for all other customers, the results should be totally compatible with the previous versions of the software. Our customers needed to be able to compare new measurements to their historical data. Hmmm, how could I be sure that my changes didn’t introduce any incompatibilities in the resulting data? This piece of code processed megabytes of data as they came in from the data acquisition hardware. I would never be able to verify its correctness by hand.

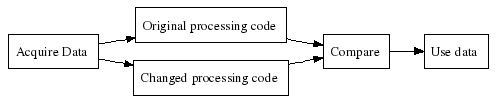

Who can verify this data fast enough? The application, of course! If it was fast enough to process the data, it was fast enough to verify the data. I restructured the affected code to look like this:

Cleaning the dungeon

At first, “Changed code” was a copy of the original code. As expected, the “Compare” stage indicated that there were no differences between the two streams.

This code was a real mess: it was hard to understand, full of low-level C pointer manipulations, long functions, function names without meaning, 1 or 2-letter variable names… To understand the code, I started to make small changes. After each small change, I would re-run the application with test data to verify that I hadn’t introduced any incompatibilities. If anything was broken, I undid the change.

After a few days of making these small changes, I had transformed the scary dungeon into a light, airy, cosy little room: the code was now simple and easy to understand. It gave the same results as the original disgusting code. No monsters had been seen or harmed during this transformation.

Now I could implement that feature. It was extremely easy and only took me a couple of hours. I used the same technique to verify that my changes were compatible if the feature was not activated.

And what have we learned from this?

This time I had learned something: you should always have tests for your code. On the next major project, we wrote a whole set of tests that exercised the code we were writing. The test called all of our methods with certain test data and print out the results. I looked at the output and see if everything was well. I ran tests every day, so that we discovered errors early. I was the TestRunner.

When I left that project, nobody ran the tests any more. It was too difficult and time-consuming to run the test application and interpret the results. They might run it once in a while if there was a serious bug, but the test was finally forgotten.

And things were back to normal: people were scared to make changes, bugs weren’t caught quickly, more bug reports came in from testers and customers … That’s how it’s supposed to be, isn’t it?

One for the road

I just don’t seem to learn, do I?

I quit!

After working for a few years for this company, I decided to leave. I had to negotiate with my manager and the HR guy how long I would have to stay on.

The manager proposed that I stay on until I finished “Project X”, a customisation of two of our products for one of our biggest customers. At this company we had a habit of starting projects with many, unclear feature requests and then piling on more features as we were developing. We were all too busy with frantically churning out code to notice the whooshing sound of the deadlines as they flew by. We felt like Mr Creosote, being fed one “wafer-thin” feature at a time, until we exploded. If past performance was an indicator, it would be at least a year before that project would be done and I could get out.

We finally agreed that I would stay on another 5 weeks, the legal minimum. I would do as much of Project X as I could in these last few weeks.

An offer he couldn’t refuse

I asked the product manager to select the few most important features that would satisfy the customer AND that I could implement in a few weeks. He was not amused; he wanted “everything”, as usual. My final offer: “either you get some features OR you get none. It’s your choice, I’m off in 5 weeks in any case”. He grumblingly took the first option and complained to everyone who’d listen about “those developers getting uppity”. I asked the product manager to select the few most important features that would satisfy the customer AND that I could implement in a few weeks. He was not amused; he wanted “everything”, as usual. My final offer: “either you get some features OR you get none. It’s your choice, I’m off in 5 weeks in any case”. He grumblingly took the first option and complained to everyone who’d listen about “those developers getting uppity”.

We selected a set of features that was both feasible and provided the customer with a coherent implementation of their requirement. The metaphor we used was: “This is like a software patch panel, so that the customer doesn’t have to waste time manipulating the wiring on the hardware patch panel.”

The knights who say ni no!

Everything had gone smoothly: no features had been added during development. Not that the product manager didn’t try, but I could now afford to say no. Everything had been done according to the company’s process, including all the documents and documentation. I had worked at a relaxed, leisurely pace and yet I had accomplished more than on any other project at that company. In the process I had refactored a particularly nasty piece of code (more on that later) and created a reused piece of code.

4 weeks later…

The product manager performed the acceptance tests. He grumbled about all those missing features. He found a few small errors. We found a major oversight in the requirements: the UI didn’t indicate how the “patch panel” was (re)wired, which was very confusing. Oops!

Next day, I fixed the small errors and we performed the acceptance tests again. Passed.

Around the process in one day

Next day, we discussed how the “wiring visualisation” feature should work, I adapted the specification document, adapted the design, modified our MVC framework, used that to update all affected UIs in both applications and we performed the acceptance tests again. Passed. We had just gone through our whole development process in a single day.

Done. That left me two days to say goodbye to everyone and buy the drinks and snacks for the farewell party. This the most fun AND productive project I’d ever done at that company. And it was the only one that finished on time. I should have quit more often!

And all those extra features? They were never implemented.

And what have we learned from this?

I left for bigger and better things. Well, not bigger and not always better, either. I still scheduled based on features. I still believed that the customer needed all the features they asked.

And things were back to normal: deadlines slipped, goalposts moved. Developers got demotivated. Except for the small (1 month or so) projects… That’s how it’s supposed to be, isn’t it?

I’ll take this task. I’ll take that task

I just don’t seem to learn, do I?

Getting a bit of a reputation

We saw here how soldiers signed up for tasks to create our division’s schedule. We expected this method to give us an easier way to create a stable and fair schedule. And it did. After a while something else happened. Our division started to get a reputation for reliability, punctuality and trustworthiness. We’d always show up on time for tasks and perform them as required. No fuss, no complaints. Our schedules were reliable and credible. It was our schedule, our responsibility to implement it well.

Sometimes, this good reputation worked against us. If you’re the duty officer and you need some more soldiers to complete a work team, where would you look for “volunteers”?

The first rule of this team is: no shouting!

We did have to educate the NCOs (non commissioned officer, the guys ranking above soldier, below officer). In NCO school they got taught that the only way to get soldiers to do something is to shout at them. We didn’t like to be shouted at. Each time we had to deal with a new NCO, we would explain these simple rules:

- You don’t shout. We can hear you perfectly.

- You don’t threaten. You can’t scare us, because we know the rules and regulations as well as you do. Or even better. In a routine, rule-based culture he who knows the rules, rules.

- You tell us what needs to be done, not how.

- In return, we’ll perform the task efficiently, without any fuss.

- That way is easiest for both of us. You know it makes sense.

Most of the NCOs learned the lesson quickly. Some never did and found that dealing with us was very time consuming and tiring. So, they started shouting more and, as a result, found us getting even more tiresome. But if they asked us to perform a task, we would self-organize to get it done quickly.

The dishes are clean? Wow, that’s novel!

The quality of the work increased. For example, when you’re cleaning dishes, it doesn’t take a lot more effort to actually make them clean. We all like to eat out of clean dishes don’t we? These were still the same boring, mind-numbing tasks. But if you sign up for a task, you might as well do it right.

This was unusual. Up until then, soldiers would do the least amount of effort they could get away with. If something wasn’t done right, that was someone else’s problem. Someone else has to eat out of the dirty dishes you failed to clean. You had to eat out of the dirty dishes someone else didn’t clean well.

And what have we learned from this?

Back in the real world, tasks were assigned to me and my teammates. When I led teams, I would assign tasks and tell team members how to perform them. Luckily, I was rarely shouted at. They teach you a lot a stupid stuff at PM school, but not something that stupid.

And things were back to normal: people did their jobs, they were committed. But without “hustle“, without that bit extra where you think about what you do and don’t just do it. That’s how it’s supposed to be, isn’t it?

Backup soldiers

I just don’t seem to learn, do I?

High availability soldiers

As described in the previous entry, the CSM had to schedule soldiers to perform all sorts of tasks. What happens when someone isn’t available to perform a task? That would create chaos and we can’t have that, can we? The solution: assign two soldiers to each task: the primary and the backup. If the primary isn’t available, the backup performs the task. That should increase the availability of the soldier resources. As described in the previous entry, the CSM had to schedule soldiers to perform all sorts of tasks. What happens when someone isn’t available to perform a task? That would create chaos and we can’t have that, can we? The solution: assign two soldiers to each task: the primary and the backup. If the primary isn’t available, the backup performs the task. That should increase the availability of the soldier resources.

Of course, this made the planning job even more difficult for the CSMs: they had to schedule double the number of soldiers, with even more potential for scheduling conflicts.

Did it work?

Not really. There were lots of primary/backup scheduling conflicts, which made the plans even more slippery. But having double the number of required soldiers assigned should have made it easier to form complete work-teams each day, shouldn’t it? No, because of a very annoying dynamic.

Soldiers had a tendency to become ill or otherwise unavailable on those days that they were assigned as primary. That meant their backup had to perform the job, but who cares? They didn’t know Joe Random Soldier who’d been assigned as their backup. It’s everyone for themselves here!

Of course, when a backup had to take on an extra job, this would have to be compensated. That meant even more schedule churn. And soldiers started to get ill when they were backups too. Imagine the chaos as the officer on duty tries to form complete teams, with all the people on his duty roster calling in sick.

A simple solution: pair soldiering

We faced the same issues when we made our own schedules. We solved it by grouping the soldiers in pairs. Each soldier paired up with someone with whom they’d been in basic training. Whenever one of them was primary, the other was backup. And vice versa.

When it came to choosing tasks, the pair chose together. This way, they could avoid primary/backup schedule clashes. We formed pairs out of soldiers who had been through basic training together because:

- they had the same seniority and thus the same priority in choosing tasks

- we reasoned that you wouldn’t deliberately welsh on someone you knew and worked with every day. If a backup ever had to replace a primary, it was easy to compensate by switching roles on the next task (of the same value). If one of the pair defaulted on their duty, the other could easily retaliate.

How did that work?

Very well. Scheduling wasn’t difficult at all: each pair just had to make sure they didn’t introduce any conflicts for the both of them. Primaries never got sick (except for one case in 1 year), so backups never had to fill in. Whenever there was a problem, we could simply “swap” tasks or roles, with minimal disruption to the schedule.

The “pair with someone from basic training” rule was useful for scheduling, but not necessary as a deterrent. With tasks swaps (see the previous story), you got other soldiers (from the same division) as backup anyway. That’s not a problem, as long as it’s someone you know and work with (and thus trust).

And what have we learned from this?

Back in the real world, there were no backups. Everyone worked on the modules they had been assigned. Some people got very possessive of their code: if the owner wasn’t available (or if they were in a bad mood), the module didn’t get changed, no matter how badly you needed the change. No-one else was allowed to (or could) change these modules. And at the end of the year, you’d get a performance appraisal for your work.

In one case (I’ll tell the full story later), I was leaving this company. I wanted to tell someone about the last project I’d worked on, but nobody wanted to listen. Finally, someone told me why: “If ‘they’ know I understand that module, they’ll assign it to me. And I’ll be stuck maintaining it, for the rest of my life!”

And things were back to normal: work had to wait to be completed, because the one programmer who knew some module was unavailable. No two modules worked alike; each of them reflected the eccentricities of their (sometimes many) authors. When people left, they took all their knowledge with them. Taking over someone else’s module felt like archaeology, even when the module was documented… That’s how it’s supposed to be, isn’t it?

How many points for a soldier?

I just don’t seem to learn, do I?

You’re in the army now

After my studies I had to perform a compulsory military service. What does a soldier do all day in peace time? Apart from the “job” you’re supposed to do (in my case, working at the data processing center), you’re mostly performing boring, menial tasks like cleaning the barracks, pealing spuds, washing dishes, guarding the base. After my studies I had to perform a compulsory military service. What does a soldier do all day in peace time? Apart from the “job” you’re supposed to do (in my case, working at the data processing center), you’re mostly performing boring, menial tasks like cleaning the barracks, pealing spuds, washing dishes, guarding the base.

Now there are lots of soldiers and lots of tasks. How do you allocate who does what, when? This was the job of the CSM (Company Sergeant-Major). Each division’s CSM had to make a monthly plan to allocate the tasks to their division’s soldiers. Combine all the division’s plans and you’ve got the work plan for the whole base.

Apart from the usual constraints (one can’t do two tasks at the same time), there were constraints on the number of tasks you could be assigned each week. There were two types of tasks: “work duty” and “guard duty”. After being on guard for 24h, you got the next day off to get some sleep. Which introduces another constraint. And you want the allocation of work to be reasonable fair. Not so easy…

A good plan is hard to find

How did that work? It didn’t.

Nobody thought the system was fair; it was always easy to find other soldiers who had considerably fewer tasks than you had. The plan changed daily as constraint violations were fixed, people complained, tasks got switched. You never knew if you were going to be assigned to perform some task the next day or not. There were always several different versions of the plan; nobody really knew which one was the “correct” one.

The result: total chaos, tasks not being performed, bad morale, poor discipline. And lots of stress for the CSMs who had to manage this chaos. And what’s the standard CSM way of solving problems? Shouting. Very loudly. It doesn’t help, but at least they feel as if they’ve done everything they could…

A simple plan

Most of us in the army data processing center were engineers or computer scientists. How could we solve the scheduling problem? With scheduling software? No, in our experience software only made things worse. We needed a simple solutionâ„¢! We made our CSM an offer he couldn’t refuse: we would fill in the work assignments for him.

We started by giving each task a number of points. The more we disliked doing that task, the more points. This depended on the type of the task and the day. E.g. a task on a weekday cost less than one in the weekend. The easiest task got 2 points; the hardest task got 7 points. From then on, it was easy: we played the “Duty Game” each month.

The Duty Game, round 1

Each month we received a duty roster to fill in. The soldier with the best maths skills assigned the points to each task and added them up. Now we knew “how many task points we had to do” this month. Our math wizard then divided this number of points by the number of soldiers in our division. Now we knew how many task points each of us had to do this month.

Then, each of us played the first round of the game, with the following rules:

- you have to put your name on as many tasks as needed to equal or exceed the required number of points.

- you may not violate a scheduling constraint

Everyone got to choose in turn. Old-timers first, rookies last. With people rotating in and out, you’d get closer to the head of the queue each month.

The Duty Game, round 2

Of course, the guys who had to choose last had a very limited choice. They might be forced to violate a constraint or pick an inconvenient date. To solve this problem, we had a second iteration. In this round, you could swap tasks with another soldier, with the following rules:

- you could only swap tasks if their number of points was (approximately) equal, irrespective of the number of tasks. E.g. I could swap a 5 point task for a 3 point task + a 2 point task.

- you may not introduce schedule constraint violations

This second round quickly and easily solved any problems in the schedule. We didn’t have a backup plan in case we couldn’t solve issues, but we never needed one. We were always able to solve the problems to everyone’s satisfaction.

Did it work?

We always filled in the plan quickly, within the time limits set by the CSM. The schedule was fair and took into account each soldier’s preferences and personal constraints. We produced a conflict-free schedule with a minimum of effort. Our monthly schedules stayed mostly constant, we (almost) never needed to change them. If we needed to change something, we would swap tasks (with the same rules as in the second round), so that only the two people involved in the swap were affected.

And what have we learned from this?

After a year, I was released back into the “real world”. I started to work as a programmer. How did I know what to work on? Well, there were project managers who would make plans for groups of developers. Lots of programmers, lots of work, lots of planning constraints to satisfy. The plans changed constantly, there were several versions of “the plan” and nobody knew which one was the “definitive one”, you had no idea what you were going to work on the next day…

And things were back to normal: chaos, work not being performed, bad morale, poor discipline. And lots of stress for the project managers who had to manage this chaos… That’s how it’s supposed to be, isn’t it?

|

Why did I get this project? Probably because no one else dared to take on this project. The main part of the coding would be deep in the bowels of the applications, written long ago. It was like a dark, dank, dangerous dungeon nobody dared to enter. There had been some stories about people going in, but they hadn’t been seen again.

Why did I get this project? Probably because no one else dared to take on this project. The main part of the coding would be deep in the bowels of the applications, written long ago. It was like a dark, dank, dangerous dungeon nobody dared to enter. There had been some stories about people going in, but they hadn’t been seen again.

I asked the product manager to select the few most important features that would satisfy the customer AND that I could implement in a few weeks. He was not amused; he wanted “everything”, as usual. My final offer: “either you get some features OR you get none. It’s your choice, I’m off in 5 weeks in any case”. He grumblingly took the first option and complained to everyone who’d listen about “those developers getting uppity”.

I asked the product manager to select the few most important features that would satisfy the customer AND that I could implement in a few weeks. He was not amused; he wanted “everything”, as usual. My final offer: “either you get some features OR you get none. It’s your choice, I’m off in 5 weeks in any case”. He grumblingly took the first option and complained to everyone who’d listen about “those developers getting uppity”.