|

|

Kevin Rutherford responded to the People vs Process entry and asked the following questions:

- Could it be that Toyota can afford to say “it’s always a process problem” because of the cultural values of their people?

- Does Weinberg’s soundbite sound plausible purely because blame and ego are so deeply ingrained in Western culture?

- Where Hansei is never associated with blaming, can there ever be a “people problem”?

Very good questions. But how do you get and sustain such a blame-free culture? Consistently seeing each problem as “a process problem, not a people problem” is part of that, I think. Of course, there’s a lot more to “The Toyota Way”.

Another example of this approach is Norm Kerth’s Prime directive of retrospectives: “Regardless of what we discover, we understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could, given what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand.” If we really want to have Hansei in the culture of most of our companies, we must first defuse all the blaming that we’ve come to expect.

The problem for many of us is that failing is generally not an option.

Marc Evers responded to the Lean vs Theory of Constraints entry and asked the following questions:

- If you always optimize everything, don’t you run the risk of optimizing something that will never be used?

- Isn’t the Theory of Constraints something like YAGNI for process optimization?

- If you keep on optimizing bottlenecks, the bottleneck will move. Is this also true when you continuously optimize everything? Is the bottleneck dynamic the same?

The Toyota Way fieldbook says that every improvement opportunity will be used. Even if it concerns a process that will disappear in a few months. Apparently, Toyota feels it more important to keep the Kaizen (“continuous improvement”) spirit alive, than to save some optimization effort. As we’ve seen in the evaporating cloud, having a “Pull” system avoids most of the problems that the Theory of Constraints warns us of.

The X vs Y blog entries seem to generate some interest. Let’s see if I can find (or create) some more conflicts…

Tags: Systems Thinking, Theory of Constraints, Lean, Toyota Way

Looking for a conflict

Lately, I’ve been studying the “Thinking Processes“. As usually happens when I discover a new solution, I want to apply it to everything. I want to play some more with the “Evaporating Cloud” (see my first attempt), a tool to resolve conflicts. Hmmm… Which conflict can I resolve today?

To optimize non-bottlenecks, or not?

There is a question that’s been puzzling me for a long time: the Theory of Constraints and Lean have conflicting advice about optimization.

The Theory of Constraints tells us that we should only optimize the bottleneck. Because the throughput of the system is constrained by the bottleneck, the only way to improve the performance of the system is to improve the bottleneck. The theory also tells us not to optimize non bottlenecks. In the best case, the optimization won’t improve the system, but it’s probable that this improvement will actually worsen the system’s performance (by increasing work in progress, inventory…). It’s quite easy to see in the “drum-buffer-rope” example.

Lean tells us to mercilessly remove waste and improve every part of the system. Toyota encourages everyone to continuously search for ways to improve ways of working. Even if it’s only a small improvement. Even if that part of the system will replaced in the near future. No improvement opportunity is lost.

This is the dilemma: “Optimize everything” conflicts with “Only optimize the bottleneck”. I like both approaches and have used them both successfully. How is it possible that two of my favourite techniques disagree? Or do they…

The evaporating cloud

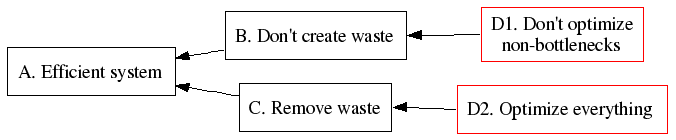

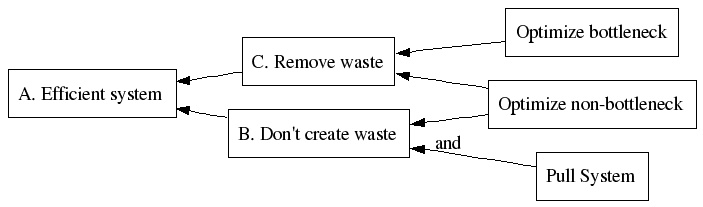

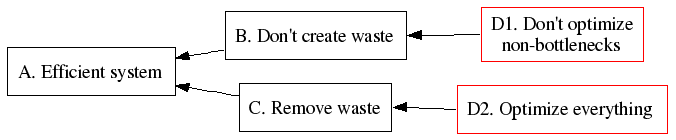

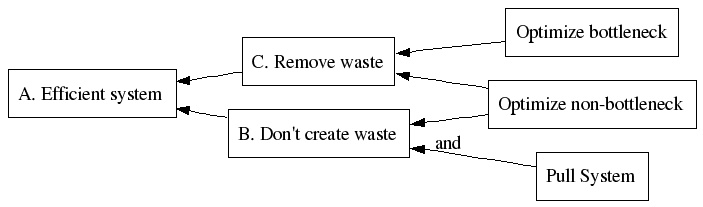

Let’s draw an evaporating cloud for this conflict:

Reading the diagram from right to left:

- We don’t optimize non-bottlenecks IN ORDER TO avoid creating waste

- We avoid creating waste IN ORDER TO have an efficient system

- We optimize everything IN ORDER TO remove waste

- We remove waste IN ORDER TO have an efficient system

- Optimize everything CONFLICTS WITH don’t optimize non-bottlenecks

Examining the diagram critically

Let’s apply the legitimate reservations:

- Clearly, “remove waste” and “don’t create waste” contribute to having an “efficient system”

- Evidently, Toyota optimizes everything all the time and their system has very little waste.

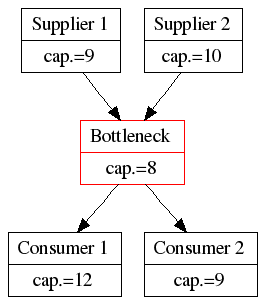

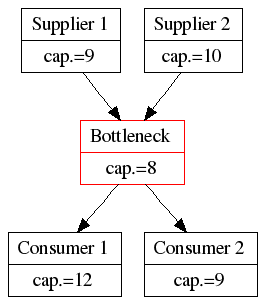

- Clearly, optimizing a non-bottleneck has no effect on the system’s throughput and increases work in progress and inventory. If we look at the diagram below, what happens if we optimize Supplier 2 to have a capacity of 12? The system still has a capacity of 8. And we’re now overproducing 4 items, which end up in inventory. Overproduction is the worst kind of waste in the Lean philosophy.

A conflict. Unless…

Optimizing a non-bottleneck results in overproduction. Unless… If we use a “Pull” system, the consumer determines the output rate of the producer. In that case, the optimized Supplier 2 still produces 8 units, but now has 4 units of spare capacity. We could use that capacity to subordinate to the constraint or exploit the constraint. By doing that, we keep inventory low and increase the bottleneck’s (and the system’s) throughput.

Restating the system

In this system we see that optimizing both the bottleneck and the non-bottleneck resources removes waste. BUT: unless we have a “Pull” system, optimizing non-bottlenecks will introduce waste. Therefore, use the ToC approach in a less mature system, with a “Push” scheduling model; use the Lean approach in a system with a “Pull” scheduling model.

I feel a lot better, now that this is settled…

Tags: Systems Thinking, theory of constraints, thinking processes, Toyota Way

Running on empty.

I just don’t seem to learn, do I?

Artificial Intelligence

Years ago, I wrote my Master’s thesis at the university’s Artificial Intelligence lab. I extended an expert system to make it learn from experience. Years ago, I wrote my Master’s thesis at the university’s Artificial Intelligence lab. I extended an expert system to make it learn from experience.

The software ran on Lisp Machines. We only had three of these machines on campus, two in the lab where I worked, another one in a lab on the other side of campus. Lots of people wanted to work on these machines. The machines were clearly a bottleneck.

There was an “interesting” way to deal with the bottleneck: the staff could use them in the day, students could use them in the evenings.

Natural stupidity

I came in each evening to work a bit on the application. Load the application, which took a while. Check the changes that the TA developing the expert system, had made during the day. And then I could work on the part of the application I had planned to work on.

Each evening the same scenario would repeat itself: I made a bit of progress and then got bogged down with a problem. No matter what I tried, I couldn’t solve the problem. I was stuck. Tarpitted. I went home.

Next morning, I looked at the previous evening’s problem. The problem that seemed so difficult the night before, was actually very simple. You had to be really stupid to not be able to solve that problem!

I finally managed to implement the system after struggling for many nights. It wasn’t a particularly great piece of software.

Stop wasting my time with time management courses

A few years later, my company sent me and my team on a three day off-site “Time management course”. That would teach us to use our work day more efficiently, they hoped. Unfortunately, the company also asked me to perform an important technology assessment that same week.

So, I had to come to the office each evening after attending the course, to finish that assessment. This useless time management course forced me to do overtime that week! Stupid course, it didn’t teach me anything!

Go home!

Years later, I managed a team. Extreme Programming was all the rage then. It all sounded very plausible. I was determined to apply the “Sustainable Pace” (then called “40 Hour week”) practice. Each evening I would do the rounds of the office to see if people were working late.

When someone worked lated, I gently reminded them to leave on time. If they were still working late the next day, I sent them home. If they still worked late the next day, I told them to see me the next day, so that we could discuss what problems they had. This allowed me to discover and fix several problems early. Code quality improved.

As usual, I had made the rule and I thought it didn’t apply to me. I still worked long hours. I got stupider by the day. Unfortunately, there was noone to tell me to go home. I had sent them all home.

And what have we learned from this?

We don’t do stupid things like that anymore, us Extreme Programming experts, do we? At the previous Pair Programming Party we tried to implement a very simple story. We were all a bit tired after a full working day, but it was such a simple feature.

Following the TDD canon, we wrote a failing unit test (several lines of code), implemented the code to make the test work (half a line of code) and expected the unit test to succeed. It failed. Whatever we tried, we couldn’t get this code and its test to work the way we wanted to. We finally gave up.

Two days later, I looked at the code and the error jumped me in the face. You had to be really stupid to not be able to solve that problem! … That’s how it’s supposed to be, isn’t it?

Lesson learned:

- Four (pairprogramming) eyes see more than two

- Four tired eyes are just as blind as two tired eyes.

Well, at least the expert system learned from experience…

Tags: agile

Thinking for a Change at SPA 2006

Marc Evers and I will host a session on the Theory of Constraints’ “Thinking Processes” at the SPA 2006 conference. Marc Evers and I will host a session on the Theory of Constraints’ “Thinking Processes” at the SPA 2006 conference.

The session is, not coincidentally, called “Thinking for a Change”, after the Thinking Processes book by Lisa Scheinkopf, that introduced me to the subject. The session is, not coincidentally, called “Thinking for a Change”, after the Thinking Processes book by Lisa Scheinkopf, that introduced me to the subject.

We will introduce “current reality trees”, “transition trees” and “future reality trees” by applying them to real problems that participants bring to the session. We will be “learning by doing” by taking small steps: explain part of the technique, apply the technique, reflect, explain another part…

We don’t have the time to deal with the “Evaporating Cloud” technique during the session, but we will run a “birds of a feather” session about it. The previous entry contains an example of the use of the evaporating cloud. Expect more examples of the techniques in upcoming entries.

The conference takes place in St Neots, Bedfordshire, from 26 to 29 March.

Some of the interesting sessions of the conference:

See you there!

Tags: SPA2006, theory of constraints, thinking processes

It’s always a people problem (Gerald Weinberg) It’s always a people problem (Gerald Weinberg)

In “The Secrets of Consulting“, Gerald Weinberg tells us that Whatever the problem is, it’s always a people problem.

All too often, problems are labeled as “Technology problems”, to hide the real problem and avoid blame. This strategy is very effective in a field like IT, where there is lots of technology churn. However, you can always trace even these problems back to people: who selected the technology and why, do people know how to use the technology, were the users of the technology consulted…

It’s always a process problem (The Toyota Way) It’s always a process problem (The Toyota Way)

The Toyota Way states that Whatever the problem is, it’s always a process problem.

Not surprising, coming from a company which has one of its principles: “The right process will deliver the right results.”

An example situation: Mike the micromanager

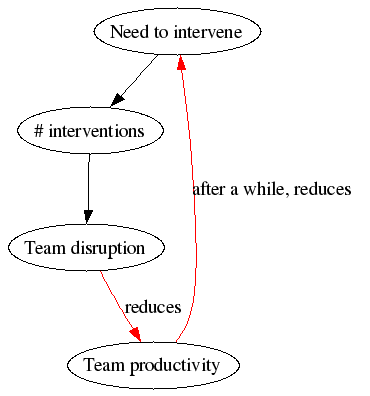

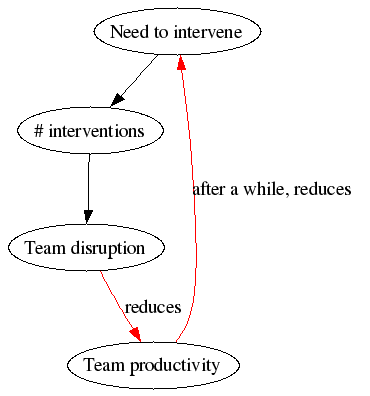

Imagine an all too common situation: someone who micro-manages their team. As the number of interventions rises, so does the disruption to team member’s flow. This reduces the team’s productivity. When the lower results become visible, this increases the need the manager feels to intervene, which leads to more interventions. And the vicious circle goes on an on…

Micromanagement as a people problem

What questions would Gerald Weinberg ask?

- Where does this need to intervene come from?

- Is the manager aware of the effects of his actions? Could we clarify this by using a Systems Thinking approach as above?

- Can we improve the way the manager and the team communicate? E.g. the manager could “batch” his requests of the team; the team could provide better visibility into the state of their work, so that the manager need not fear that “things are getting out of control”.

- How do the team members react to the interventions? Are they acting incongruently themselves?

Micromanagement as a process problem

What questions would Toyota ask?

- What is wrong with our hiring or promotion process, that put this manager in a situation he wasn’t able to handle?

- What is wrong with our training and coaching process, that we left this manager in a difficult situation without any help?

- What is wrong with our Genchi Genbutsu (go see on the workfloor) process, that this manager’s manager didn’t go and see how the team was, so that he could see the problem?

- What is wrong with our Hourensou (report, inform, consult) process, that this manager didn’t inform his manager of the problem and consult him for ways to solve the problem?

- What is wrong with our evaluation and “Stop the line to fix mistakes”, that nobody stopped to report the problem and find its cause?

People or Process? Evaporating the cloud

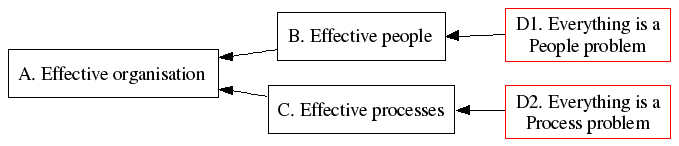

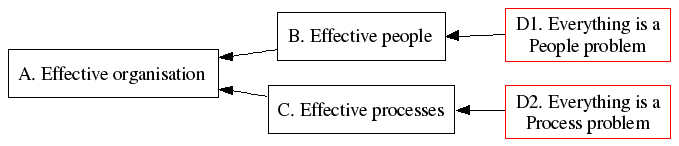

We clearly have a conflict: either every problem is a people problem or it’s a process problem. The “Thinking Processes” provides us with the “Evaporating Cloud” technique to examine and resolve such conflicts.

How do you read this diagram?

- In order to have “An effective organisation” (goal) we need “Effective people” (requirement 1), because the effectiveness of the people determines the qualities of the result (assumption 1)

- In order to have “An effective organisation” (goal) we also need “Effective processes” (requirement 2), because effective processes enable people to work well together (assumption 2).

- In order to have “Effective people” (requirement 1), we need to “Treat every problem as a people problem” (prerequisite 1), because this will help us focus on solving the fundamental people problems and not get sidetracked by superficial symptoms (assumption 3).

- In order to have “Effective processes” (requirement 2), we need to “Treat every problem as a process problem” (prerequisite 2), because this will help us focus on continuously improving our processes and thereby making our solutions available to the whole organisation (assumption 4).

- There is a conflict between D1 and D2: either all problems are people problems OR all problems are process problems.

How can we resolve the conflict?

- Are the relationships between goal and requirements valid? I think so. I believe we need a combination of effective people and processes to succeed. Take away one of them and you can’t have an effective organisation (if you have effective people, they will probably grow a process anyway).

- Are the relationships between prerequisites and requirements valid? I believe the only way to be effective is to be continually be solving problems, be they people or process problems.

- Are the assumptions correct? I believe so, I can’t find any counter-examples for the moment.

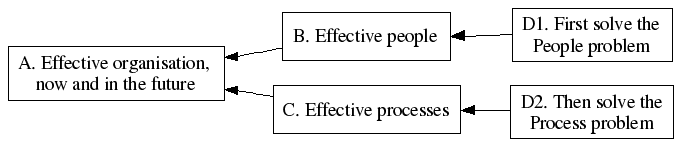

- Why can’t D1 and D2 co-exist? Are they really mutually exclusive? What’s the assumption behind this? Hmmmmmm. Let me think…

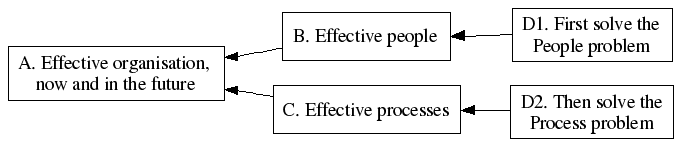

Imagine that both statements are true: Every problem is a people problem AND a process problem. Would this assumption lead to a contradiction? Let’s see what we would do in Mike’s case:

- First, we could call in Jerry Weinberg and resolve this manager and team’s issues, so that this team can work effectively.

- Then, we could call in a Toyota sensei to question the processes that led up to this problem and failed to detect and correct it. They would help us to improve the processes, so that this kind of situation could be avoided in the future, so that in the future, all teams can work effectively.

I believe this resolves the conflict: every problem is a people problem that must be solved now AND an underlying process problem that must be solved, so that this problem doesn’t reoccur in the future. That means we have to clarify our goal: “To have an effective organisation, now and in the future“. With these changes, the diagram looks like this:

Reconciling people and process, present and future

Both types of problem solving have their place. We need to deal with the problems that people are having now. We need to continuously improve our processes so that these problems won’t reappear for other teams in the future.

An analogy I like is that improvement needs to be like a ratchet: relentless reflection and continuous improvement (Hansei & Kaizen) drive the gear wheel forward; processes encode our growing and changing knowledge to act as the “click” that prevents the wheel from turning back.

Tags: Systems Thinking, theory of constraints, thinking processes, Toyota Way

|

Years ago, I wrote my Master’s thesis at the university’s

Years ago, I wrote my Master’s thesis at the university’s