|

|

Operational Excellence AND Customer Intimacy, but not at once

In the previous blog entry, we saw how one company resolved the conflict between operational excellence and customer intimacy. They found a way to have both. But we didn’t implement both at the same time.

We first went for Operational Excellence. First we standardised, made things reliable, made work repeatable, not only in production but also in IT. The existing product definitions were inconsistent and complex. This made our code complex because we had to treat every product as a special case. Over a period of about one year all the product definitions and the code were refactored to new standardised forms. All of this happened while the system was in production and new features were released every two months. We got very good at refactoring and migrating without disrupting because we did it so often, in small steps.

A similar ‘refactoring’ happened on the production floor. Product line by product line was tackled: work cells clearly labeled, clear flow lines from input to output established, work in process limited… When I first went to see the production floor I nearly got lost between the piles of work in process and it was hard to see what was going on. After the changes, the area looked a lot more spacious and it was clear at a glance what was going on.

Once we had the production and development system under control, we started to think about customisation and getting more intimate with our customers.

Effectiveness AND Alignment, but not at once

This reminded of Alan Kelly’s blog entry about the “Alignment Trap“. In summary: we want our IT organisations to be effective (do things right) and aligned with business objectives (do the right things). Unfortunately, most organisations do neither.

If we want an organisation that does the right things and does them right, what strategy should we follow? Based on a study, Alan conjectures that it’s best to focus on effectiveness first, alignment second. First learn to do things right, then do the right things.

Managed and Agile, but not at once

I encounter a similar situation in many coaching and consulting engagements. Organisations want IT teams that are reliable, predictable and can be trusted to deliver as promised. And they also want them to be agile, deliver faster and respond to change. Lean and Agile can get you there.

What’s the first step? Usually, we need to bring things under control, clear away the clutter, reduce chaos, limit task switching, limit work in process and make things visible. This often involves “anti-agile” or “anti-lean” measures such as batching support, analysis and design work to avoid task switching and installing strict change management and issue prioritising to keep focus. I always get lots of complaints and get accused of “not being agile” from people who are used to the chaos and suddenly find that the team no longer asks “How High?” when they yell “JUMP!” Those who stop jumping find that they get a lot more done and that the results are better. They are less stressed.

Once we have the process under control, we can start improving the flow.We know how to do things, we can start to go a bit faster, in smaller steps; we can disrupt the stability to improve a bit. And then we find a new stability and so on.

Heijunka

Heijunka is one of the often forgotten Toyota Way principles. It means “levelling the load”, working at a steady, regular, sustained and sustainable pace. It means planning the work so that there’s a good balance between flow and the load on people and machines.

Large companies who impose just-in-time deliveries to their suppliers without levelling their orders abuse their suppliers. Teams who randomly request clarifications for stories burn out their Product Owner. Teams who push out releases faster than their customers and users can accept them throw away value.

Heijunka means making and keeping work humane.

Which small step can you take to make your work more humane?

Decisions by consensus

One of the Toyota Way principles is « Nemawashi », take decisions by consensus.

Building consensus is a slow process, but it’s necessary to get everybody on board before taking a decision. Otherwise, the implementation will be delayed and (unconsciously) sabotaged by those who didn’t agree or weren’t involved.

It’s not just about building support for your ideas. The consensus-building process solicits ideas and review from everyone involved so that the final idea is usually a lot stronger than the original.

But there’s one big misunderstanding about consensus.

Consensus doesn’t require Compromise

It’s tempting to dilute our idea to reach consensus, ensure that everyone gets a bit of what they want, so that they’ll agree to go along. It’s tempting to dilute our idea to reach consensus, ensure that everyone gets a bit of what they want, so that they’ll agree to go along.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In “Extreme Toyota” the authors show how Toyota embraces conflicts and doesn’t settle for compromises. They identify six contradictions that are central to Toyota’s way of working:

- Moving gradually and taking big leaps

- Cultivating frugality while spending huge sums

- Operating efficiently as well as redundantly

- Cultivating stability and a paranoid mindset

- Respecting bureaucratic hierarchy and allowing freedom to dissent

- Maintaining simplified and complex communication

“This AND that” sounds better than “This OVER that”… I want to have my cake and eat it too 😉

Enter the business consultants

A few years ago I worked on a project that automated the whole value stream of a business unit. The main challenge was that the different departments had conflicting needs. No surprise there.

One of the conflicts was between the production department that did the work on customer demand and the sales department that sold contracts for doing the work to the customer . The production department needed standardised products with little variation so that they could work efficiently, predictably and hit their Service Level Agreements; the sales team needed customised products so that they could tailor their offering precisely to what the customer needed.

This is a classical conflict. The business consultants on the project called this “Operational Excellence” versus “Customer Intimacy“. And the consultants said we had to choose. It’s one or the other, you can’t have both. It’s like Henry Ford’s saying: “You can have any color car, as long as that color is black.”

Examining the conflict

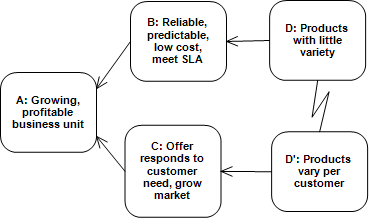

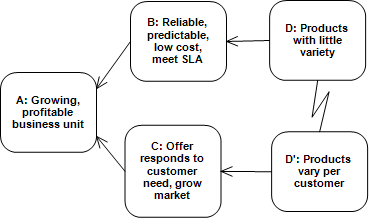

It’s clear, you can’t have both standardised and customised at the same time. There’s a clear conflict. But we have a tool to deal with conflicts: the Conflict Resolution Diagram. Let’s apply the tool:

The diagram says:

- To have a growing, profitable business unit (A) we need to sell what the customer needs (C) and deliver it reliably and cheaply (B).

- To produce reliably, predictably at low cost and to hit the Service Level Agreements (B) we need products with little variety (D).

- To create an offer that responds to the customer’s need and to grow our market (C) we need to vary our products per customer (D’).

- Conflict: we can’t have little variation (D) and a lot of variation (D’) at the same time, but we need both.

Questioning assumptions

We deal with the conflict by questioning the underlying assumptions. Can we find fault with our logic? Bill Dettmer recommends to restate the relationships in “extreme wording”. For example:

- There’s absolutely no way to have both low and high variability at the same time! Well, duh!

- The only way to be profitable and reliable is to have low variability! Well, it was hard to fault this reasoning as this company operated on large volumes with low margins and tight competition.

- Customers always need special cases! Not always, but customers were no longer satisfied with one-size-fits-all offers. If this company couldn’t offer customised products, the competitors would be more than willing to get a new customer.

- We could have low variability and yet vary per customer if only we didn’t have so many customers! Going niche wasn’t an option for economical and legal reasons.

We looked at it every way possible and couldn’t find a fault with the reasoning until…

Finally, some clarity

The Logical Thinking Processes have a set of “Legitimate Reservations”, a set of critical questions we should ask. The first one is simply called “Clarity“: is the meaning of every word and sentence clear to everybody?

Now, we had already noticed that the different departments seemed to have different definitions for the same word. There were even differences in the way they described the different products to us. Were we talking about the same thing?

The breakthrough came when we asked “What do you mean by ‘Product’?” A product for the Production department wasn’t the same thing as a product for the Sales department. And the accounting & finance department had another definition of product. But… That’s not a bug; it’s a feature: if a Production-Product is different from a Sales-Product, can we have Production-Products with low variation and Sales-Products with high variation?

After a lot more work we came up with a way to standardise Production-Products on a small set of “building blocks” and let Sales create Sales-Products by mixing and matching the building blocks according to customer need. Then we mapped Production-Products onto Accounting-Products. And everybody got what they wanted: Operational Excellence AND Customer Intimacy.

Embrace conflict

We didn’t settle for a compromise, but spent the time to really think through our conflicts and come up with a solution that satisfied all needs. A conflict can be an opportunity to come up with an innovative solution.

You don’t have to settle for compromises if you think about it.

Picture of Bonsai by A. Marques. Thank you.

Is estimating due to lack of trust?

Rob Bowley’s “Estimation Fallacy” session at SPA 2009 contained some discussion about trust. In particular, this pithy statement was made:

Estimates are due to the lack of trust between the business(*) and development team.

There have been a number of descriptions of “estimation-less” approaches. Is it simply a case of lacking trust?

It’s probably a bit more complex than that.

Valid reasons to estimate

Why would we estimate the effort and cost of a project, a release, an iteration, a feature?

To evaluate if the benefit of the project outweighs the cost. Say we have an estimate of the value a project or product may bring. I’m prepared to pay you 1.000.000€ if you deliver certain product. Do you do this project? Only if it will cost you less than that amount to deliver it. Of course, we should try to break the product down in smaller Minimal Marketable Features so that we can deliver sooner and get value earlier.

To make scope tradeoffs. Say we have a given budget and time: we need to show a demo at an industry event in 3 months with the current team. Which features shall we keep, which can we postpone? Which features will give us most “bang for the buck”? Of course, we start by prioritising by value, but three lower valued/lower cost features may have more effect than one higher value expensive feature.

To know how to distribute resources over multiple projects. Say we’ve got 20 projects we could start and we have 50 developers. Which project(s) do we start? How do we know where the developers will have the most effect? Of course, we start the fewest possible projects simultaneously, but there’s a limit to the number of people that can work on one project.

To make reliable promises to others. “Can we deliver this game before Christmas? If so, we need to get the marketing campaign started.” Of course, it would be easier if we were all in the same multi-functional team or if we had a real cross-company value stream. But sometimes we do have to coordinate with others or agree on contracts.

To know when to exercise our Real Options. Real Options tells us we need to make a decision at the optimal decision time. This is the deadline minus the implementation time of the most costly option. How do we know the implementation time?

No estimation? Really?

I agree that spending inordinate amounts of time on estimating is a waste of time. But no estimation? If I look at the “estimation-less” methods I see a few different approaches:

- Break down the work in approximately even-sized amounts of work. In effect, you can say that each item now has a cost of ‘1’. Then you can simply count the number of items and use throughput and cycle time to make your estimations. How do you know that the items are approximately even-sized?

- Count the number of user stories, even if you know they have different sizes. In the end, it doesn’t matter much, some stories will go faster, some stories will go slower. Over a release many of those differences cancel each other out. What do you call the number of stories you typically deliver per release?

- Give each item a high level estimate (in points, gummi bears or t-shirt size) and track (or estimate for the first few releases) how many of those you can reliably deliver. Concentrate on those items were estimates matter.

The only really estimation-less method I see is one where features are prioritised purely based on value and then pulled for implementation one by one, without caring how long it would take to implement. I think this is what’s described by Joshua Kerievsky. Even then, he talks about micro-releases, so the features must have been broken down into reasonably small pieces.

That’s about how I work on projects where I’m both developer and customer: user stories are prioritised by value and released in micro releases. The features are small enough to be implemented in a couple of hours. In any case, I set a timebox and revert if implementation takes too long. I know the value; I know how much I want to spend; most of the time I correctly estimate that the cost of the feature is within my budget.

Trust: necessary but not sufficient

Estimations are useful but fraught with many problems. Trust between everyone involved helps a lot, but it doesn’t eliminate the need for estimates in most circumstances. Let’s look at some of the issues related to estimating and see what the root causes are. Maybe we can do something about the root causes.

And why don’t we talk about estimating (business) value?

(*) I really, really hate the use of the expression “The business“. IT, the development team is part of the business. If we want more trust, can’t we start by seeing them as one team?

Software projects are difficult because…

I’ve heard this said several times over the years:

Software projects are difficult because software is so easy to change.

Other engineering and building projects are seemingly easier because they deal with “hard to change” stuff like bricks, mortar and steel.

I heard this statement again at Rob Bowley‘s SPA 2009 “Dealing With the Estimation Fallacy” goldfish bowl discussion about estimation. Rob has written up the outputs of the session, but sadly there’s nothing more about this fascinating statement.

I find it difficult to accept this statement. Surely, the ease of change must be an advantage? It means we can exercise our Real Options later, that we can change our mind when we know more? It means that we can correct mistakes and wrong assumptions more cheaply? It means we can keep our creations relevant in a changing world?

So, to make software projects easier we just need to…

If the previous assertion is true, then making software projects easier is easy.

Make software hard to change so that software projects become (a little bit) easier.

Forget “embrace change”! From now on, I’ll make software hard to change. Not that I have to do much to achieve that, I can create hard to change software without thinking. 🙂

Hm. I still don’t understand why easy to change software makes projects hard. Do you know why?

Some effective ways to make software projects easy

The goldfish bowl came up with some more ideas about change.

1. Use only reliable, thoroughly tested technology that serves your people and process

One remark was that we make things difficult for ourselves through technology churn. Technology and tools change rapidly. Unfortunately, most of these changes are no improvements. But we don’t have to stay on that treadmill. Some time ago a new programmer in the team complained: “Why don’t we use technology X? It’s new!”. My response: “That’s exactly why we don’t use it. Yet.”

When I’m in charge of a project, we will only use a new tool or technology when it’s thoroughly tested and when everyone in the team understands it. We’ll first try the new tool on prototypes or small internal projects so that we can discover the hidden pitfalls. And even then I need to have a backup solution on hand if the new thing doesn’t work. As Weinberg says: “Anything new never works”. As the Toyota Way says: “Only use reliable, thoroughly tested tools that support people and process”.

2. Don’t reuse. Use.

Another remark was that we write too much custom code from scratch. We could reuse more or implement standard packages. My experience with this is mixed.

Standard packages can work IF they deal with a well-known, stable domain where you don’t want to differentiate yourself from your competitors. For example, you probably don’t want a custom accounting package, unless you’re Enron. But is a standard package really the best way to run your manufacturing plant? Maybe when you don’t want continuous improvement. If the slogan is “It’s easier to change your company to match the software than to change the software to match your company”, then you’ve got some really hard to change software. Those projects don’t look easy, though.

I’m no fan of frameworks. The penalty for “colouring outside of the lines” is too steep. Most packages and frameworks are “80% solutions”: great for the first 80% of your project, hell for the last 20%. For example, I like Ruby on Rails, but it takes me so much effort to do something differently than what the Rails developers think is the right way. As a result, I’ve seen mostly productivity decreases when using frameworks, even the ones I wrote 😉

What does work:

- Writing software for use, not for reuse. When I write TDD code, refactor and remove duplication I end up with useable code. A surprisingly large amount of it ends up to be useable in other projects. Three or more instances of this happening and it becomes worth spending time extracting the common code and maintaining it in a library.

- Using libraries, especially small, focused libraries with technical components. It’s a pleasure to be able to download a Ruby Gem, have a quick look at the source, write some unit tests against it, use it. For example, it took me about an hour to integrate the Akismet anti-spam service into my wiki. Since then it has stopped lots of spamming attempts on the many wikis I maintain. Great value for money!

These are just two small measures. They don’t make software projects easy. But they do avoid unnecessary difficulty.

Les cinq premiers pas… Les cinq premiers pas…

Aujourd’hui, Portia et moi présentons une nouvelle session, “Les cinq premiers pas pour devenir agile” au XP Day Suisse à Geneve. C’est une présentation courte et interactive (les participants jouent 5 jeux) qui introduit cinq “outils” que nous utilisons quand nous commencons à travailler avec une équipe.

Plus de nouvelles après le congrès.

Cinq outils… et plus

Si vous voulez apprendre ces cinq outils et plein d’autres pour aider votre équipe a réaliser plus de résultats, devenir plus agile et s’amuser plus, la formation “Agile en Pratique” de Zenika est toute faite pour vous. Si vous voulez apprendre ces cinq outils et plein d’autres pour aider votre équipe a réaliser plus de résultats, devenir plus agile et s’amuser plus, la formation “Agile en Pratique” de Zenika est toute faite pour vous.

Vous aimeriez appliquer les méthodes agiles. Comment les appliquer dans votre équipe, sur votre projet ? Comment faire la transition vers les méthodes agiles? Cette formation répond à toutes ces questions. A travers des exercices, des jeux et des simulations vous expérimenterez les techniques agiles. Vous saurez comment, pourquoi et quand les appliquer afin d’améliorer la qualité du résultat et du travail de votre équipe.

Rendez-vous les 21 et 22 Avril à Paris!

The five first steps to become really agile

Portia and I present the “Five first steps to become really agile” at the Swiss XP Day. This new session presents five simple “tools” that we use when we start to work with a new team.

This is the first session that we developed first in french. We’ll translate it in English and do a tryout soon. Then we’ll publish the session on our Agile Coach site with the other games we’ve made.

More about the session when it’s published.

|