|

|

Sunday

Attended a workshop on Use Cases. The audience contained both use case users and sceptics, which resulted in some heated discussion. Not unusual for an SPA session. I did get some useful ideas to apply at work.

The day ended with a barbecue and drinks sponsored by Cincom, who valiantly keep on making, selling and using Smalltalk. One day, when I grow up, I want to do a real Smalltalk project again.

Monday

Marc Evers and I hosted the “Thinking for a Change” session this morning. The session went well: 3 out of 4 participants were able to find the root cause of their problem AND come up with some useful things to do about it. The problems were quite diverse:

- a software development coach having trouble communicating and working with the managers of the team

- having a good balance between home life and work

- how to reduce the spiraling costs of change in an application

- a business struggling to find enough money to survive the next few months, until their product is out.

In the evening we did a “Birds of a Feather” session on evaporating clouds. Again, two very different cases. One of them got to a start of a conclusion; the other managed to uncover a whole set of assumptions. To really resolve it, both parties would need to go through the exercise, to get a better understanding of the other party’s position, reasoning and assumptions.

In the bar, after dinner and drinks, I joined another group making a Current Reality Tree and a Future Reality Tree. Today was a Thinking Processes day.

Tags: Systems Thinking, agile, SPA 2006, Theory of Constraints, Thinking Processes

Kevin Rutherford responded to the People vs Process entry and asked the following questions:

- Could it be that Toyota can afford to say “it’s always a process problem” because of the cultural values of their people?

- Does Weinberg’s soundbite sound plausible purely because blame and ego are so deeply ingrained in Western culture?

- Where Hansei is never associated with blaming, can there ever be a “people problem”?

Very good questions. But how do you get and sustain such a blame-free culture? Consistently seeing each problem as “a process problem, not a people problem” is part of that, I think. Of course, there’s a lot more to “The Toyota Way”.

Another example of this approach is Norm Kerth’s Prime directive of retrospectives: “Regardless of what we discover, we understand and truly believe that everyone did the best job they could, given what they knew at the time, their skills and abilities, the resources available, and the situation at hand.” If we really want to have Hansei in the culture of most of our companies, we must first defuse all the blaming that we’ve come to expect.

The problem for many of us is that failing is generally not an option.

Marc Evers responded to the Lean vs Theory of Constraints entry and asked the following questions:

- If you always optimize everything, don’t you run the risk of optimizing something that will never be used?

- Isn’t the Theory of Constraints something like YAGNI for process optimization?

- If you keep on optimizing bottlenecks, the bottleneck will move. Is this also true when you continuously optimize everything? Is the bottleneck dynamic the same?

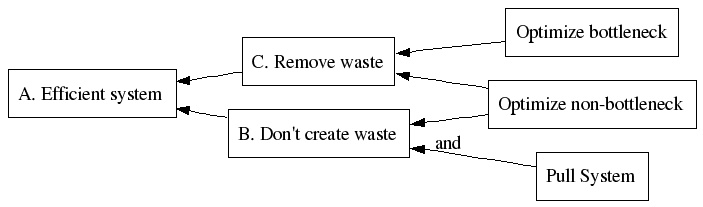

The Toyota Way fieldbook says that every improvement opportunity will be used. Even if it concerns a process that will disappear in a few months. Apparently, Toyota feels it more important to keep the Kaizen (“continuous improvement”) spirit alive, than to save some optimization effort. As we’ve seen in the evaporating cloud, having a “Pull” system avoids most of the problems that the Theory of Constraints warns us of.

The X vs Y blog entries seem to generate some interest. Let’s see if I can find (or create) some more conflicts…

Tags: Systems Thinking, Theory of Constraints, Lean, Toyota Way

Looking for a conflict

Lately, I’ve been studying the “Thinking Processes“. As usually happens when I discover a new solution, I want to apply it to everything. I want to play some more with the “Evaporating Cloud” (see my first attempt), a tool to resolve conflicts. Hmmm… Which conflict can I resolve today?

To optimize non-bottlenecks, or not?

There is a question that’s been puzzling me for a long time: the Theory of Constraints and Lean have conflicting advice about optimization.

The Theory of Constraints tells us that we should only optimize the bottleneck. Because the throughput of the system is constrained by the bottleneck, the only way to improve the performance of the system is to improve the bottleneck. The theory also tells us not to optimize non bottlenecks. In the best case, the optimization won’t improve the system, but it’s probable that this improvement will actually worsen the system’s performance (by increasing work in progress, inventory…). It’s quite easy to see in the “drum-buffer-rope” example.

Lean tells us to mercilessly remove waste and improve every part of the system. Toyota encourages everyone to continuously search for ways to improve ways of working. Even if it’s only a small improvement. Even if that part of the system will replaced in the near future. No improvement opportunity is lost.

This is the dilemma: “Optimize everything” conflicts with “Only optimize the bottleneck”. I like both approaches and have used them both successfully. How is it possible that two of my favourite techniques disagree? Or do they…

The evaporating cloud

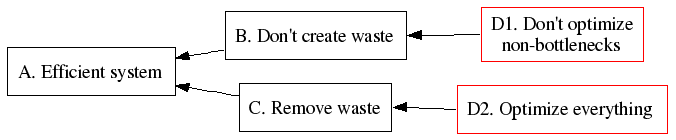

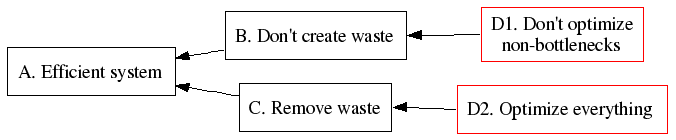

Let’s draw an evaporating cloud for this conflict:

Reading the diagram from right to left:

- We don’t optimize non-bottlenecks IN ORDER TO avoid creating waste

- We avoid creating waste IN ORDER TO have an efficient system

- We optimize everything IN ORDER TO remove waste

- We remove waste IN ORDER TO have an efficient system

- Optimize everything CONFLICTS WITH don’t optimize non-bottlenecks

Examining the diagram critically

Let’s apply the legitimate reservations:

- Clearly, “remove waste” and “don’t create waste” contribute to having an “efficient system”

- Evidently, Toyota optimizes everything all the time and their system has very little waste.

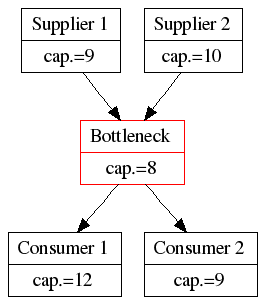

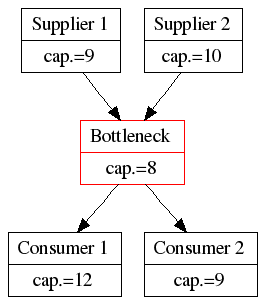

- Clearly, optimizing a non-bottleneck has no effect on the system’s throughput and increases work in progress and inventory. If we look at the diagram below, what happens if we optimize Supplier 2 to have a capacity of 12? The system still has a capacity of 8. And we’re now overproducing 4 items, which end up in inventory. Overproduction is the worst kind of waste in the Lean philosophy.

A conflict. Unless…

Optimizing a non-bottleneck results in overproduction. Unless… If we use a “Pull” system, the consumer determines the output rate of the producer. In that case, the optimized Supplier 2 still produces 8 units, but now has 4 units of spare capacity. We could use that capacity to subordinate to the constraint or exploit the constraint. By doing that, we keep inventory low and increase the bottleneck’s (and the system’s) throughput.

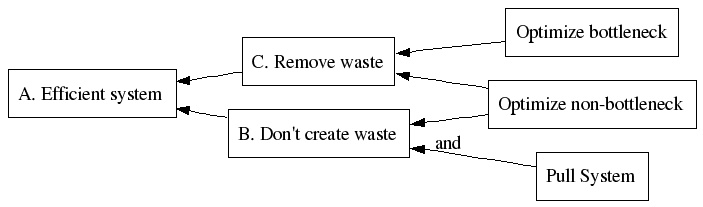

Restating the system

In this system we see that optimizing both the bottleneck and the non-bottleneck resources removes waste. BUT: unless we have a “Pull” system, optimizing non-bottlenecks will introduce waste. Therefore, use the ToC approach in a less mature system, with a “Push” scheduling model; use the Lean approach in a system with a “Pull” scheduling model.

I feel a lot better, now that this is settled…

Tags: Systems Thinking, theory of constraints, thinking processes, Toyota Way

(Fr)Agile Software Development. Ha ha!

Detractors of Agile Software Development sometimes use the term Fragile Software Development. It’s an easy pun, you don’t have to think too hard about it. And then you can dismiss the whole idea of agile software development without a further thought.

This accusation is mostly aimed at Extreme Programming. XP has a set of interlocking practices that reinforce and balance each other. Take one away and the whole house of cards comes crumbling down.

XP is fragile. And that’s how it’s supposed to be.

Huh? Agile: good! Fragile: bad! Surely?

What if that fragility contributes to XP’s agility?

Let’s look at another fragile method and all the ways it can break: Lean. Let’s count the ways we can shut down a Lean plant:

- Just in time delivery: if one delivery from one supplier is late, what little inventory you have runs out very quickly.

- Everyone can stop the line: if someone discovers an error, the whole line is shutdown while the cause of the error is removed (actually, the line shuts down incrementally: first one cell, then a group of cells, then the line, depending on how long it takes to fix the problem).

- Pull: there are very small buffers of work in progress between cells, regulated by Kanban cards. If one cell fails to replenish the buffer, the other cells quickly shut down due to lack of input. Ideally, you have “one piece flow”, no buffers!

- Small batches: each production run produces only small batches, which are consumed quickly. If the process that produces the batches breaks down, the consumers quickly break down due to lack of resources.

And yet… every metric and statistic available clearly indicates that Lean plants are more efficient and production lines break down less often than “traditional” plants with lots of safety margin.

Making the system more fragile: lowering the water level to expose the rocks

In between cells or parts of the production line, there are small buffers of unfinished work (see the “Drum-buffer-rope” entry) that protect a consumer from variations in output of its producers. The Toyota Way describes how the size of these buffers is determined: by using the lower the water level to expose the rocks technique.

Whenever a process runs smoothly, the size of the buffer is reduced. If the system keeps working smoothly, the buffer is reduced again. This continues until the system breaks down. The buffer is enlarged to the previous value and the root cause of the system breakdown is researched. When that problem has been solved, the buffer is reduced again.

The metaphor that gave this technique its name goes like this: imagine you’re sailing a boat. Below the water surface, there are rocks, but you don’t know where they are. If the water level is high enough, you’ll never hit any rocks. If you gradually lower the water level, you will hit the highest rock. Now you can remove that rock and you can sail freely again. To hit (and find) more rocks you lower the water level again. The metaphor that gave this technique its name goes like this: imagine you’re sailing a boat. Below the water surface, there are rocks, but you don’t know where they are. If the water level is high enough, you’ll never hit any rocks. If you gradually lower the water level, you will hit the highest rock. Now you can remove that rock and you can sail freely again. To hit (and find) more rocks you lower the water level again.

Fragility keeps you on your toes

How would you act if a mistake could shut the whole plant down? You would make damn sure that everything is in place to avoid mistakes or to fix them very quickly. You’d try to find and fix root causes of problems. You would constantly look to improve and refine your processes. You would actively search out problems. That is… IF you worked in an extraordinary, learning organisation.

If you work in the average company, you would be scared to do anything for fear of being blamed (and fired). That’s one of the reasons that the Toyota Way says “Whatever the problem, it’s never a people problem, it’s always a process problem”

A while ago, I had a discussion about how to handle a daily build failure. I advocated letting the whole team work on fixing the build problem, before they started to work on new features. Someone else proposed to let one developer fix the build, so that the others could get on with their work. He thought I was a bit excessive, extreme even. Now why would I want to waste good developer’s time? Maybe to make our process a little more fragile, to make the cost of a build break a bit higher, so that we would think that little bit harder about how to avoid the root causes of broken builds.

XP is fragile. XP is Lean

XP has even more ways to break down than a Lean plant. Let’s list a few:

- What if the customer can’t supply stories fast enough (just in time)?

- What if your story cards get lost/blown away/stolen? (I get this question a lot)

- What if your tests don’t catch all the errors?

- What if the build breaks a lot?

- What if developers don’t sign up for stories/tasks?

- What if… (your favourite method of breaking down here)

What keeps XP projects alive?

- A team with a common vision and open communication.

- Discipline to practice all the agreed practices, not just the easy ones. Even when there’s pressure. Especially then.

- A blame-free environment, so that you can solve problems and learn.

- Reflecting on what you do.

- Constantly looking for ways to improve.

- Being open-minded to accept solutions when you find them, even if that means you’re not doing XP by the book. Especially then.

And that’s just for starters. Who knows where you would end up if you kept doing that? Just imagine… How fragile can you make your process?

Tags: agile, theory of constraints, lean, Toyota Way

Thinking for a Change at SPA 2006

Marc Evers and I will host a session on the Theory of Constraints’ “Thinking Processes” at the SPA 2006 conference. Marc Evers and I will host a session on the Theory of Constraints’ “Thinking Processes” at the SPA 2006 conference.

The session is, not coincidentally, called “Thinking for a Change”, after the Thinking Processes book by Lisa Scheinkopf, that introduced me to the subject. The session is, not coincidentally, called “Thinking for a Change”, after the Thinking Processes book by Lisa Scheinkopf, that introduced me to the subject.

We will introduce “current reality trees”, “transition trees” and “future reality trees” by applying them to real problems that participants bring to the session. We will be “learning by doing” by taking small steps: explain part of the technique, apply the technique, reflect, explain another part…

We don’t have the time to deal with the “Evaporating Cloud” technique during the session, but we will run a “birds of a feather” session about it. The previous entry contains an example of the use of the evaporating cloud. Expect more examples of the techniques in upcoming entries.

The conference takes place in St Neots, Bedfordshire, from 26 to 29 March.

Some of the interesting sessions of the conference:

See you there!

Tags: SPA2006, theory of constraints, thinking processes

|

The metaphor that gave this technique its name goes like this: imagine you’re sailing a boat. Below the water surface, there are rocks, but you don’t know where they are. If the water level is high enough, you’ll never hit any rocks. If you gradually lower the water level, you will hit the highest rock. Now you can remove that rock and you can sail freely again. To hit (and find) more rocks you lower the water level again.

The metaphor that gave this technique its name goes like this: imagine you’re sailing a boat. Below the water surface, there are rocks, but you don’t know where they are. If the water level is high enough, you’ll never hit any rocks. If you gradually lower the water level, you will hit the highest rock. Now you can remove that rock and you can sail freely again. To hit (and find) more rocks you lower the water level again.