|

|

Theory of Constraints session at XP2005, participants were given an experiential crash course in the Theory of Constraints. They then had to apply their new knowledge to solve real world problems.

They did this in 3 groups. Each group had a “customer”, the others played “TOC consultant” to help the customer to understand and improve their system.

|

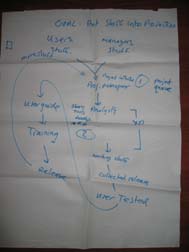

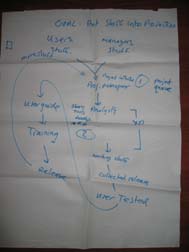

This is the output of one of the groups: it gives an overview of the whole process from requirements, over analysis, development, testing, writing manuals, training and finally putting “stuff” into production.

Click to enlarge the image

(picture courtesy of Marc Evers) |

Remarks about the poster

The goal of the system is to “Put stuff into production“. An IT system can only generate value when it’s put into production use and users are actually using it (well). Hence the User Guide and training before releasing. Part of the value in releasing a system is the feedback and ideas you receive to improve the system, hence the loop back to project initiation.

The bottleneck of this system was actually two bottlenecks (indicated as [1] and [2]), which ocurred at different times during the project. Bottleneck [1] holds the system back at the beginning of the project; bottleneck[2] holds the system back near the end of the project. It’s not as bad as a “constantly shifting constraint”, but we need to focus in different areas depending on the phase of the project.

Notice how the part marked with “XP” is between two bottlenecks. This is something that has been observed in many (if not most) XP projects: XP has very effective techniques to exploit, subordinate to and elevate a development team bottleneck. If you apply the techniques, the development team’s throughput improves a lot and it’s no longer the bottleneck. The bottleneck shifts. And who’s the bottleneck then? Usually the Customer (role) becomes the bottleneck, either in keeping the team fed with stories or in accepting the stream of finished features. Or both, as in this case.

XP in a nutshell, from a Theory of Constraints perspective:

- XP assumes that the development team is the bottleneck

- IF this is correct, XP increases the throughput of the development team and thereby shifts the bottleneck to the Customer

- If this assumption is not correct…

In the session we chose one bottleneck to concentrate on, the one the customer wanted to remove the most.

Our newly graduated “TOC consultants” suggested several ways to exploit, subordinate and elevate these bottlenecks, coming up with some novel ideas that their customer could apply to this situation. What are some of the interventions we could suggest here?

- We have two bottlenecks, before and after “XP”. They are bottlenecks at different times in the project. If they are different resources, they could help each other out: bottleneck [2] resources can help (subordinate to) bottleneck [1] resources at the beginning of the project; and vice-versa at the end of the project. E.g. testers can help analysts at the start of the project by devising acceptance tests; analysts can help testers to perform and analyze acceptance tests.

- We have a non-bottleneck resource, the “XP” team. They could subordinate to both bottlenecks, by spending some of their slack time in helping the bottlenecks. One way of doing is to assign one person from the development team to “follow the release”. This developer helps the analysts to write stories and clarify acceptance tests. They also help the testers during acceptance, the writers writing manuals, the operators installing the software. Their primary job is to smooth the interface between the development team and the world outside the team. They have a good overview of both the functional and technical content of the release. While this developer works at the end of the release, another developer starts preparing the next release and follows that release through to the end. This is a “rolling wave” planning, which is great for continuity and is a good way of “leveling the load” (One of the 14 principles of the Toyota Way). You do need people in the development team who are skilled at interfacing with other teams, who understand both the functional and technical side of a project…

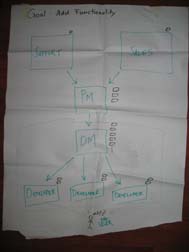

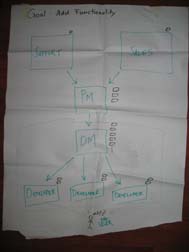

This is the output of the second group. The “bottleneck” of this system is easy to spot: everything has to go through 2 people. The stacks of work in front of each person indicates how much work in progress accumulates in front of each resource. This is the output of the second group. The “bottleneck” of this system is easy to spot: everything has to go through 2 people. The stacks of work in front of each person indicates how much work in progress accumulates in front of each resource.

Click to enlarge the image

(picture courtesy of Marc Evers)

Some remarks

The goal of the system is to “add functionality” to an existing system. This functionality creates value only when it’s delivered to the customer. But that seems to take an inordinately long time, as the snoozing customer would indicate.

The bottleneck is the Development Manager (DM), with the Project Manager (PM) as bottleneck-in-waiting. All the work has to go through these two people. In the case of the Development Manager, all work goes through them several times: the DM carefully prepares and assigns the work to the developers, helps them design and develop and then the work has to come back for review(s).

How can we improve this situation?

- Currently, the PM explains the required functionalities to the DM. The DM then explains the functionalities to the developers. We could exploit the DM by having the PM explain the functionalities to the DM and developers at the same time. This could help break the “barrier” which now exists between business and development.

- If a few developers have more experience, they could subordinate to the DM by helping other developers and reviewing their code.

- We could elevate the constraint by hiring someone else to take on some of the duties of the DM or by training the most experienced developer(s) to take on some of the DM work.

However, these interventions might not be easy. It’s a stressful, difficult job, being the bottleneck. But it also make one very important. Having to delegate some of the work might be seen as “not being up to my job” or reduce the bottleneck’s importance.

The “barrier” in the system could be caused by the DM wanting to “shield” the team from the rest of the organisation. This way, the DM controls everything that goes in and out of the team. Some of the TOC interventions might reduce the amount of control the DM has. This too might be a touchy subject.

I do have a question about this diagram. How does the software get from the developers to the end user? We saw that the code goes back to the DM, for review. What happens next? Is there a Q/A procedure? Does the software get packaged, distributed or installed?

You’ve been applying the Theory of Constraint’s 5 Focusing Steps and you’ve been able to increase throughput of your system/organisation. But you’re running out of ideas to get more throughput. What now?

Try the 6th Focusing Step: Change The System

Changing a system is hard. You’re up against years worth of accumulated rules, regulation, processes, tacit knowledge about “the way we do things ’round here”. Like Laurent says many of these rules have accumulated over the years. Maybe they were effective at the time, but they failed to adapt to a changing world and are now holding back the organisation.

And people don’t like change.

As that eminent business consultant Machiavelli noted: “He who wants to change the organisation will only get lukewarm support from those who stand to gain from the change. He will get fierce opposition from those who gain from the current situation“.

How can you make changes easier? Here are some tips that sometimes work for me:

- Involve those who will be affected by the change in shaping the change. Nothing worse than having a change foisted upon you.

- One thing at a time. If you change several things at once, the change becomes very complicated and it’s hard to tell what worked and what didn’t. If you perform regular, incremental changes, people get used to the rythm of change.

- Let people “taste before they swallow”. This is an expression by Virginia Satir (via Jerry Weinberg and Nynke Fokma). If you encounter a new idea, have a taste of it. If you don’t like it you can always spit it out. Only swallow it when you like the taste. Propose that people try the change for a set period, after which there will be an evaluation. The change is instituted if the evaluation is positive. Make sure that the evaluation is genuine and not a rubber-stamp process.

- Trust me, I know what I’m doing. This is a tricky one… When people are afraid of a change, a little show of confidence can pull them over the line. And now you’ve put yourself on the line…

I’m still (slowly) adding stuff to the Theory of Constraints series on my site.

There are 5 focusing steps:

Okay, that’s really 6 steps.

Is that the end of it? At the XP2005 session on the Theory of Constraints we discussed a further step when the “5 Focusing Steps” run out of steam.

More about Step 6 tomorrow.

And then I’ll write up the results of the Toyota Way session at XP2005

I’m writing a series of notes on the “Theory of Constraints”, based on the “I’m not a bottleneck! I’m a free man!” sessions at XP2005 and SPA2005.

Why did I get interested in the Theory of Constraints?

- It gives me a different perspective to look at systems and organisations

- The Theory of Constraints is very simple. But the conclusions one can draw from it are often wonderfully counter-intuitive, yet very effective

- It is a complementary tool to “Lean Thinking”: ToC tells you what to optimize, Lean tells you how to optimize. ToC focuses the system optimization effort where it has the most effect.

- ToC is a whole-system method. Local optimisations often have detrimental global effects. ToC helps me look at the whole system and then take action at the local level (the bottleneck).

Read more about it:

|