A simple requirement

Imagine this situation: the CIO of a large company decrees that from now “all applications we develop must be browser based“. This becomes a non-negotiable constraint for every new project.

Imagine this situation: the CIO of a large company decrees that from now “all applications we develop must be browser based“. This becomes a non-negotiable constraint for every new project.

Unfortunately, a browser platform is not the best platform for all types of applications or all environments. A browser based application may not deliver the best user experience or support intensive workloads. It may be hard (or impossible) to access peripherals. It may be impossible to clearly show complex data sets. And when the network goes down, everybody’s work grinds to a halt.

But all the nice developers and project managers say “Yes boss!” and struggle to find workarounds for these difficulties, to satisfy the users. All of these workarounds make development and maintenance more complex. Users make do with what they receive and add more workarounds to deal with the deficiencies in the applications.

The real requirements

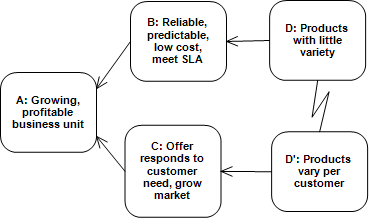

What he really meant was that from now on “all applications we develop must run on a small number of standard environments, be easy to deploy to all our users and centrally managed so that development, release and application support costs stop growing.” What’s the difference between this statement and the previous one? This statement sets a goal and constraints within which creativity can flourish. The first statement stifles creativity and stands in the way of achieving the real goal.

What he really meant was that from now on “all applications we develop must run on a small number of standard environments, be easy to deploy to all our users and centrally managed so that development, release and application support costs stop growing.” What’s the difference between this statement and the previous one? This statement sets a goal and constraints within which creativity can flourish. The first statement stifles creativity and stands in the way of achieving the real goal.

How do we find out what the real goal is? Because someone had the courage to ask “Why?” until it was clear what value we were generating for whom. As the “Discovering Real Business Requirements for Software Project Success” book says:

A requirement describes some value we need to deliver to someone.

Do your “requirements” fit this definition? Why not?

The value of analysis

The difference in value and cost can be staggering. The first statement costs the company lots of money and frustration from everyone who uses, develops and supports hobbled, complex applications. It’s a world of compromises. It doesn’t have to be this way. The second statement gives us a fighting chance to achieve the goals.

All it requires is someone to play the role of analyst to help the customer clearly describe what they need. Someone who acts like a detective to discover the real motives and issues.

A good analyst creates options and keeps them open as long as possible. The “Discovering Real Business Requirements for Software Project Success” book helps to get to the core of the problem. This fits well with a quote from “The Toyota Product Development System: Integrating People, Process and Technology“:

- Classical product development reduces the number of solutions early.

- Lean product development reduces the number of problems early and leaves as many solutions available as possible, for example by set-based development or by using tradeoff curves.

Is there someone who has the courage and skill to ask the right questions? Who has the tenacity to dig until they find the real business requirements?