|

|

A potential new bottleneck

Last week we noticed that some of our users didn’t know some features were available or were unsure how to use the new features in the previous release. So, we spent some time explaining some of the features.

This is a timely warning: our ability to effectively transition the software into production use could become a bottleneck. This is both a good and a bad thing:

- It means that our bottleneck, the development team, has been elevated to a level that’s nearer the capacity of the users to accept new features. This is good: our efforts to elevate the constraint are starting to work.

- Our capacity to train users and the user’s capacity to accept new features might become the new bottleneck. This is bad news: we don’t want the bottleneck to get out of our control.

This is a typical pattern for agile processes: the development team is elevated and after a while the customer, who subordinates to the development team (as the XP customer does), becomes the bottleneck. Suddenly, the customer can’t write stories fast enough to keep the team occupied; releases are implemented so quickly that the users can’t keep up with the flood of new features.

What to do?

Before the users become the new bottleneck, we need to take measures to elevate them so that the bottleneck doesn’t shift. What are we going to do?

- We have regular meetings with our key users who follow up new developments. We need to make these more “hands on”: show the users how new features work, let them experiment some more.

- Training and transition to a new release is handled by people in the users’ organisation. We can support them more during final acceptance testing and transition to the new release.

- We can hold an “end of sprint demo”, like Scrum prescribes to show the new features (and how they’re to be used) to a wider audience than the key users.

- Each release is focused on one group of users. For example, the current release contains mostly features for the commercial people. They will need some training to use the new release. Other groups will see only a few minor changes, so that for them the application doesn’t change too much.

Release less often?

Some have suggested that the problem is caused by us releasing too often. We release every two months. Should we release less often? I don’t think so: we used to release every 6 months and that caused big acceptance, transition and training problems. In comparison, today’s problems are insignificant.

I would suggest to release more often, establish a regular rhythm of changes. Have each release contain fewer changes, changes that appear shortly after the users ask for them and they’re fresh in their mind. Get a regular rhythm going on the “drum“, increase the “takt time”, level the load to reduce the waste due to unevenness.

Making change routine

People don’t like to change. They like routine and predictability. How can we make change easier? Regular “Kaizen” events, regular retrospectives to steer the process establish a rhythm of change. If you review and improve your process each month, every month, people become accustomed to the change.

If you want to change the routine, make change routine

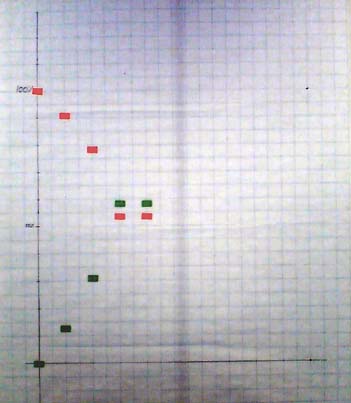

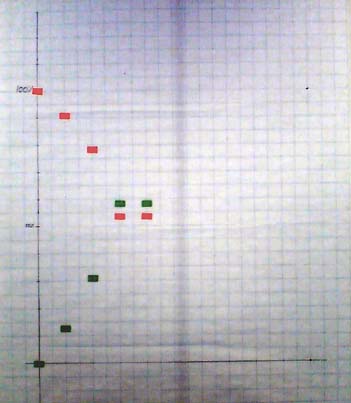

The project burn up/down chart

Our team has a very public burn up/down chart. This is where we stand today.

A short reminder: A short reminder:

- The red line tracks the burndown of estimated story work to do

- The green line tracks the delivery of estimated story value

What happened in the past two weeks?

Two weeks ago, both graphs went sharply up/down. The value chart a bit steeper than the cost chart, because we work on the highest value stories in the beginning of the project

Last week the chart was flat. No story completed this week. Oooops….

Why?

- One story counted two weeks ago turned out to be incomplete. Added some more tests to make the problem apparent, completed the implementation. No extra points, as they were already counted. If we hadn’t completed the story before the end of the week, we would have subtracted the effort and value.

- We’re all working on big, 4-5 point stories. When these complete we’ll have another big jump on the chart. That’s another disadvantage of big stories, they don’t help us level the load and they make tracking less smooth. Maybe we’re in trouble, but we won’t see quickly. We’ll only know next week, when these stories are expected to finish.

- Some of our users seem to be unclear on what new features are available and how to use them, so we spent some time explaining how the application works.

Lessons learned:

- Spend more time on tests, especially acceptance tests

- How could we have broken down these stories in 2-3 point parts?

- User acceptance of new features could become a bottleneck. Read more….

Big VISIBLE chart

People passing by and looking at the chart came up to me and asked “Hey, what’s wrong? Your graph is flat.“. Now that is instant visibility into the state of the project. Passers-by know at a glance when we’re doing well or badly.

Not bad for a tool that cost almost nothing and takes 10 minutes a week to update…

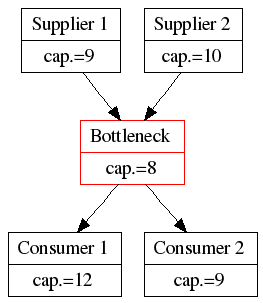

If you believe the Theory of Constraints, you know a few things:

- the throughput of your system is determined by the throughput of your bottleneck

- you should keep the bottleneck working at 100%

- you should keep the non-bottlenecks working at less than 100%, so that they don’t generate wasteful work-in-progress or are unable to cope with fluctuations.

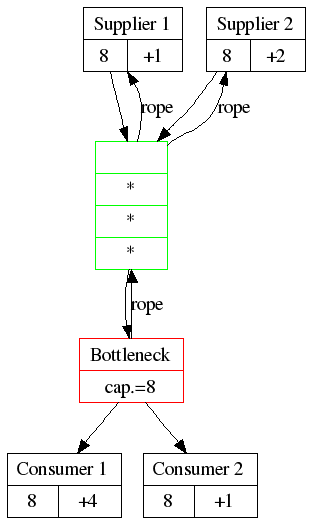

How do the non-bottlenecks know how fast they should work, without having a global coordination? By using the “Drum-Buffer-Rope” technique.

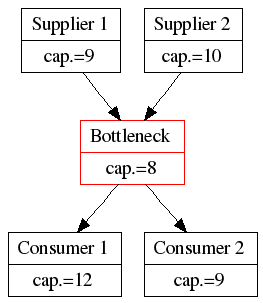

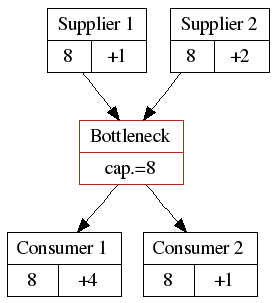

The system

The Drum

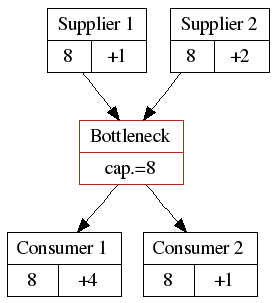

The bottleneck determines the speed at which the system works. This bottleneck can produce 8 items per unit of time. Therefore the bottleneck acts as a drum, beating the rhythm that the whole system should follow, like a drummer on a galley slave or the drummer of a marching band. The system has a rhythm of 8, so all participants in the system should follow the rhythm. This is one way to Level out the load. In Lean Thinking, this is called the “Takt Time”.

So, now we have everybody working at 8 items per unit of time.

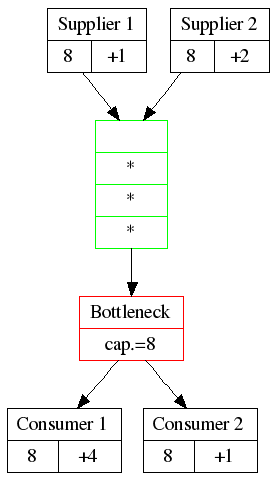

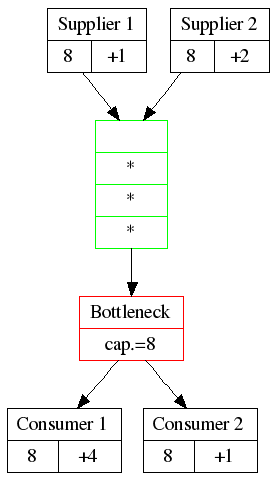

The Buffer

But what if supplier 1 or 2 can’t produce exactly 8 items? The bottleneck will be starved and we lose precious throughput. That can’t be allowed to happen. Therefore, put a buffer of raw material in front of the bottleneck, so that it never has to wait.

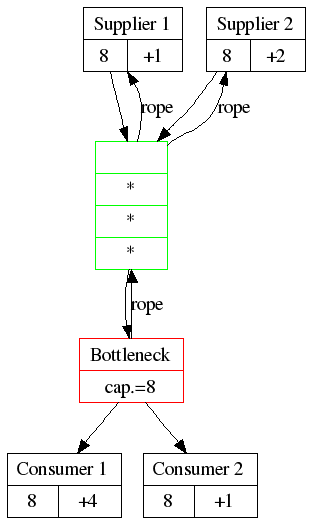

The Rope

Supplier 1 and 2 won’t always be perfectly in lockstep with the Bottleneck. We don’t want the buffer to become too big or too full, because then we have a lot of work-in-progress (and all the problems of cost, quality and overhead that generates). The bottleneck needs to limit the size of the buffer. Therfore, let the bottleneck signal to its suppliers when it has consumed an item and therefore should receive one item. Each time the bottleneck has consumed something, they ‘pull a cord’, which signals that a fresh item should be delivered. This is ‘Pull Scheduling‘

Spare capacity

We can see how suppliers and consumers need a bit of spare capacity:

- If the suppliers don’t have spare capacity, they will never be able to re-fill the buffer if something goes wrong

- If the consumers don’t have spare capacity, they won’t be able to handle fluctuations in output from the bottleneck and may thus delay processing bottleneck output.

Only Consumer 1 has a lot of spare capacity (+4). They might spend some of that capacity on other work, as long as they keep enough spare capacity to deal with the bottleneck’s output.

What does all that have to do with writing software?

Well, an IT project is a system that transforms ideas into running/useful software, where different resources perform some transformation steps. Each resource has a certain capacity and the steps are dependent on each other. And there’s certainly variation. Look quite a bit like the systems above.

Let’s see if we can apply Drum-Buffer-Rope to software development…

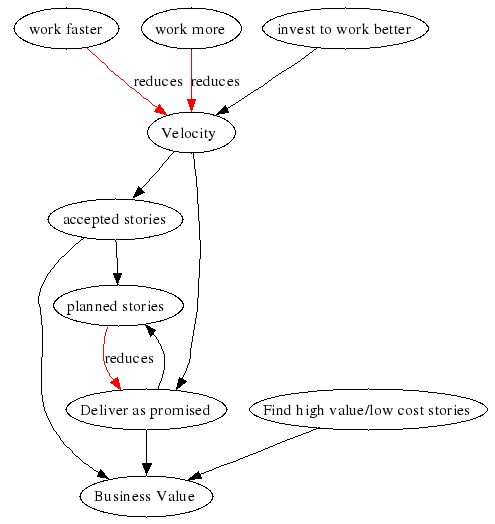

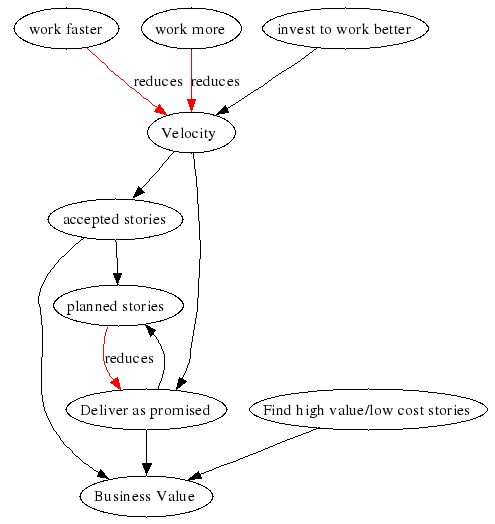

Faster. Faster, faster, faster! as David Byrne sings manically in “Air”.

In previous entries we saw how an XP team is doomed to be on a mad treadmill that spins ever faster: the team commits to delivering as much work as the previous release (the team’s velocity). They try to improve their velocity to deliver a little more than promised. If they succeed, their velocity has gone up and they commit to delivering that much in the next release. And they try to improve their velocity again… And on and on.

Does it ever stop? If they fail to deliver all the promised stories by the end of the release, their velocity is lowered: only finished and accepted stories are counted. Next iteration they commit to a little less work, which should give them some time to analyze what happened and try some improvements. If they planned by business value only the lowest value stories are not delivered; the value of the release will still be near the expected value.

In my experience, working faster or working more hours does not increase the number of stories that get accepted. On the contrary, it is the surest way to reduce your velocity.

Use Velocity to evaluate investments

How yo you increase velocity? By investing in working better:

- Writing unit tests to design better and to guard against regressions

- Refactoring code to make the design better and the code easier to change

- Pairing to spread knowledge, techniques and conventions

- Regular reflection in “Retrospectives” or “Kaizen events to review and improve the process, tools and techniques

- Holding reviews, either formally or by pairing to improve code quality and spread knowledge

- Writing automated acceptance and performance tests

- Involving customers in defining and testing the software

- Buying better tools (but only reliable, thoroughly tested technology, that serves your people and process)

- Harvesting usable code

- Go get some training, go to a seminar, go to a conference

- Do something fun, relax

- Perform an experiment, try out a wacky idea

- …

And how do you know you investment worked? Your velocity goes up. That’s one more reason to have short releases: you get quick feedback on whether your investment. If it doesn’t work, stop and try something else.

Micro-investements

Typical for agile methods is that they use micro-investments: make a small investment, see what the effect is, decide on your next investment. Unit testing, pairing, refactoring, acceptance testing… require some daily effort, some discipline. Regular retrospectives evaluate the results of the investements and decide where to invest next. Thus, if you make a “wrong” investment, you haven’t lost much effort and you at least gain some knowledge.

Another advantage of micro-investements is that they can be taken at a much lower level than major investments: many of the decisions above can be taken by individuals or the team itself, without having to go through formal investment procedures.

Of course, the danger with micro-investments and local improvements is that local optimizations worsen global performance unless you use a “whole system” approach like Systems Thinking, the Theory of Constraints or Lean Thinking.

Big investments

“Classical” approaches tend to go for larger investments, in more upfront (analysis, design, architecture) work, frameworks, product lines… in an effort to look at the whole system and to avoid rework. In my experience, as long as you don’t get it completely wrong at the start, you will get where you need to be, in a timely and cost-effective way by building in and using regular feedback.

There is one area where it’s not wise to invest too little: in determining the real needs of the users/customers. What is the real problem? What is the best way of solving the problem? Software typically is only a small part of the solution, if it’s part of the solution at all. What else do you need? Is there value to created? Does the expected value exceed the expected cost? What is the required investement? Is the return justified? These questions should be asked before the project starts, and throughout the project. That’s what the “Find high value/low cost stories” in the systems diagram is all about.

Remember:

- A system that is not used has no value

- The cheapest system is the one not built

The wish to improve Velocity must be motivated by a drive internal to the team. It can’t be mandated from the outside. If you try to push velocity up, you might achieve that at the expense of your real goal: creating more value.

Who’s satisfied by achieving a ‘repeatable’ process? The only process worth having is an optimizing one. We need people who always want to do better. Because better is more fun

If we reward people based on how high their velocity is, we’re in fact rewarding people who work hard. Or who game the the system. Assuming we trust the developers to be honest with their estimates (and there are plenty of forces helping them stay honest), what’s wrong with rewarding people who work hard?

Well, working hard is not The Goal of our team. Our goal is to create value for the people who pay for our hard work. If we want to optimize our system, we should be very clear about our goal and keep it firmly in mind.

Fortunately, value is pretty easy to measure and track IF each story has a value estimate by the customer. Just like we can measure the effort we put into the release by counting the story points of accepted stories, we can count the business value points of the accepted stories. And that’s exactly what we track on the burn up/down chart. As this chart is displayed where everyone can see it, we’re always reminded of our goal. Our goal is to:

- Create the highest possible business value in each release…

- …for the lowest possible cost per release

Therefore, we should be rewarded on the amount of value we release. As long as it isn’t released and used, the software’s value is zero.

“Hey, that’s not fair! We’re being rewarded based on value estimates made by the customer? What if the customers don’t know the value? What if they’re wrong? What if they game the system to lower the value? What if…?” Well… you do trust your customer to do a good job, to be honest, to be competent and to make an honest mistake from time to time, don’t you? If not, stop reading this blog and do something about it!

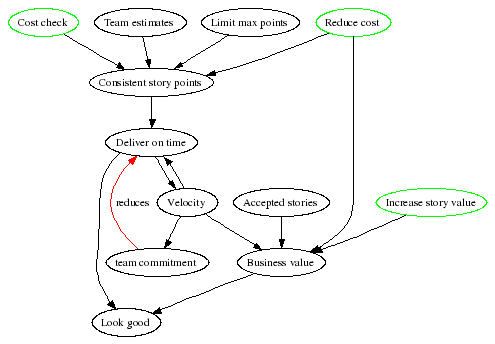

Like story point estimates, business value estimates should be consistent. Developers are allowed and encouraged to ask for the reasoning behind the value estimate. This nicely balances with the way the customer asks for the reasoning behind the story points estimates of the developers. But it’s ultimately the customer’s reponsibility to get the value right.

Customers and developers work together to maximize story value, like they do to minimize story cost. Before and during the planning game they should look critically at all the stories. Can we do this in a simpler way? Is there a way to get more value out of this story or to get the value sooner?

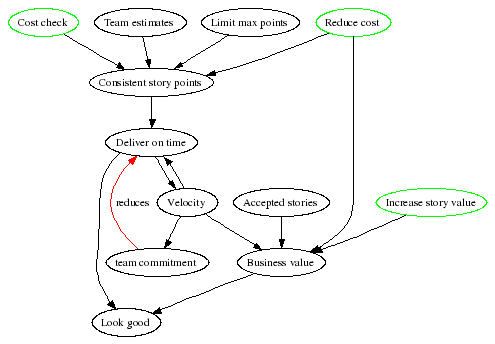

In this diagram we see that increasing velocity no longer makes you look good. Instead, producing more business value makes you look good. One of the ways to produce more business value is to genuinely increase the team’s velocity. Inflating story costs will not bring more value.

As in the previous diagram, if the team can deliver on time, their velocity will be a bit higher than planned. This means they will take on a little more work, commensurate with their increased velocity. But this reduces the odds that they will deliver on time next time, unless they find creative ways to increase their velocity.

We’ll see more about velocity in the next entry.

|

A short reminder:

A short reminder: