|

|

I’m sorry, I can’t help you because the system is down

How many times have you heard this apology? Often, the apology is “The system is down again.” In some places the system is always down around certain times and you get the same apology every day.

Why are we suprised when systems are unavailable? There will be bugs, mistakes and scheduled downtime. We should not be suprised the system is down, we should expect it.

Some time ago, an IT architect asked me during a job interview if it was possible to build reliable systems out of unreliable parts. My response:

The only way to build a reliable system is to build it out of unreliable parts (or systems)

If you want to build a reliable system, you have to be aware that all its subsystems are unreliable. This allows you to take appropriate measures, like building in redundancy.

We need a paper process

A smart manager I once worked with insisted that every business-critical automated process also required a backup “Paper Process”. The Paper Process defined how the work would be done when (not if) IT systems were down, with nothing more complicated than pen and paper (and a battery-powered calculator if really needed). When systems were unavailable everybody knew what they had to do to keep the business ticking over as if nothing happened. They also knew how to catch up when the systems were available again. In this case, it was clear who the bottlenecks were, so the other people subordinated by entering the backlog of data on paper into the system. Did I mention that this department used less automation than other similar departments, yet had a better track record of delivering on time, was more efficient and brought in more money?

Defining an alternative Paper Process was relatively easy, because we really understood the real business requirements of our customer. Since then I use this as a test of my understanding of the real requirements: could I implement the requirements with nothing more than paper and pencil? If you have real requirements (and not a solution in disguise) it’s easy to define several different implementations.

Since that project I learned more about processes. If I had to do this project again I would do it the other way round: implement the Paper Process first and ask what, if anything, we would need if the Paper Process broke down. Maybe a whiteboard is enough.

The thing I hate most about myself is that I don’t want to change

The first XP book was very important for me. It changed the way I work. It changed my life.

I still apply the practices to improve the way I work. The principles have helped me to make my work more fun, sustainable and successful. The values have helped me to do worthwhile work that delivers value.

But “Embrace Change“? I don’t like change.

How to avoid change

I avoid change on my projects by

- Really understanding the needs of customers, stakeholders and users. Those needs change from time to time, but not very frequently if we really get to the core of what these people value. I get accused of doing Big Upfront Design or Analysis, even in companies seemingly doing Waterfall. Why waste so much time upfront, can’t we start building yet? Customers don’t know what they want anyway, so why try to discover what they need?

- Not committing to decisions too soon, applying Real Options. If we commit later by delaying decisions to the last responsible moment and gather more information, we need to come back on fewer of our decisions. I do get called a procrastinator. Real leaders take charge, take decisions!

- By not being distracted by useless technology churn. Simple, reliable and known tools and technology in our toolkit let us concentrate on adding value. I do get called a dinosaur, not up to date with the latest framework or fad du jour. Real geeks only work with the latest 0.1 version of technologies that are so complex that we can spend months unraveling their intricacies (and bugs). I need a well-padded resume with all the latest technologies to get that next job when the shit hits the fan on this job.

- By making sure we consider supporting processes and users in our value analysis. All too often we focus on the shiny business value generating processes but forget that these can’t work unless people can perform the unglamorous supporting jobs that make these value streams possible. I do get called a Waterfall analyst, who wants to explore every nook and cranny of the system before we can start building. Real Agile teams deliver Business Value, cash quickly. Why waste time with non-business value-adding processes like getting the product into the hands of the user or managing the system to keep it relevant?

- By making a plan (not a schedule) of the goals we want to achieve in the future so that we have a guiding vision when we travel the path. I do get called an old-school project manager who wants to control and stifle the creativity of his “resources”. You can’t be agile if you have a plan.

Projects with fewer changes are a lot easier and less stressful than those with many changes. These projects implement Heijunka. They deliver value surely and steadily. I like that.

Embrace risk reduction and new information

I welcome any change which reduces risk. We continuously identify our main risks and find ways to avoid them. For example, we discover that there’s simple alternative way of doing something. We can use that as our backup strategy if the planned way of doing the work doesn’t get ready in time. For example, we first implement a very basic implementation of a business process and iteratively refine it, so that we’ll always be ready to release by the deadline. Of course, we have to use that extra time that Real Options gives us to actively seek out information and reduce risk.

Embrace increased flow

I welcome any change which can increase flow, get us to release faster and get the cash flowing sooner. For example, we can start by statisfying a subset of stakeholders and users. We can focus on on value stream at a time. We can mercilessly pare down what is really needed to achieve goals. We can get rid of wasteful checks, approvals and delays. We increase quality to decrease changes due to rework.

Embrace value increase

I welcome a change that increases value. For example, “Exchange Requests” let the customer increase the value of our work. If the customer wants to add a feature to a release, they first have to remove an equivalent amount of work from the release. The customer will only perform the swap if the new feature has more value than the one swapped out. So, for equal (or lower) cost, we deliver a product with higher than initially expected value.

Embrace cost and investment reduction

I welcome a change that reduces cost or investment. I welcome a new, simpler way of achieving a goal. I welcome reducing scope as we discover that we can simplify business processes. I welcome a reduction in “dimension” as we discover that we can satisfy user needs (for now) with less exhaustive or refined implementations. I welcome a way to reduce the amount of work in process.

I’ll get me coat then…

Can I be Agile if I don’t Embrace Change? Can I be Agile if I value people and their interactions AND processes? Can I be Agile if I insist on customer collaboration AND a contract? Can I be Agile if I only want to respond to beneficial change AND follow a plan? Can I be Agile if working software is not the solution or only a small part of the solution? Can I have my cake AND eat it too?

Where do I go to hand in my Agile badge?

If anybody needs a Waterfall coach, let me know. I can change. I’m agile 😉

Takt time

Takt time is the rate at which customers buy a product. Takt time determines the speed at which a Lean manufacturing runs. For example, say we sell 576 units of product A. If we have a 8 hour shift, we need to make 72 units per hour, or 1.2 units per minute. We have 50 seconds per unit.

Every step in the production process must now deliver their contribution to the product in 50 seconds.

What if there’s a step that can’t deliver in 50 seconds? Then we have a bottleneck. We’ll produce and sell less than we could. We apply the 5 focusing steps to increase the bottleneck’s capacity so that they can deliver in 50 seconds or less.

What if there’s a step that can deliver in less than 50 seconds? They still deliver every 50 seconds, even if they have to slow down. If they delivered more frequently, we’d build up lots of work in process as other steps can’t use its output faster than once every 50 seconds. Or we might build unsold goods.

Slowing down? Isn’t that inefficient? Yes, but we’re not optimising the efficiency of a single step. We’re optimising the whole value stream. If a step has a lot of spare capacity, this could be used to work on another product, but only if it doesn’t endanger the delivery of the first product.

Using Visual Management, the value stream tracks actual production rate regularly. The steps won’t run perfectly as clockwork, there will always be some variation. The production rate displays allow everybody to react (speed up, slow down a bit) to keep to the takt time. The takt time works as a metronome that synchronizes musicians.

Takt time isn’t (always) the drum beat

In Theory of Constraints, the Drum-Buffer-Rope system synchronizes the speed at which each step in production runs. The “Drum Beat” is the rhythm, the steady pace at which the slowest step (the bottleneck) runs. The rest of the system works to that beat. Again, no use producing faster than the bottleneck because we’ll only create more work in process.

The two concepts are quite similar and I sometimes confuse them. There’s one clear difference:

- takt time is customer-focused, outward looking

- drum beat is bottleneck focused, inward looking

If the customer is the constraint, a base (if not outspoken) premise of Lean, takt time equals the drum beat and drum-buffer-rope implements customer pull.

Takt time in software development

What is the equivalent of takt time in software development? If you’re Microsoft, you know approximately how many copies of Microsoft Office are bought every day. You could run your disk duplication and packaging plant at this takt time. But that’s not what I want to talk about.

Takt time = the rate at which you release a new product (version) to users

How often do you put new, valuable features in the hands of your users? Every day? Every week? Every month? Every quarter? Every year?

The logic of slow takt times or how to kill all your Agile teams with one simple decision

Most teams I work with, including Agile teams, have long release cycles. Long by my standards. Some of this is under control of the development team, but the release cycle is often dictated by other concerns. Often, operational teams (systems engineers, DBAs, support) reduce the number of releases.

Operational teams are often stressed, in fire-fighting mode and jerked around as projects miss deadlines and make last-minute changes. To reduce the load and ease the pressure, they reduce the number of releases. Fewer releases means more complex and error-prone releases, as more features are batched up in one release. These releases require more effort and have more issues. Fixing and patching those issues requires more work. Business people, under pressure to generate more value faster push harder to get features out of the door. Corners get cut, features get released under the guise of fixes. More work. The logical reaction is to reduce the number of releases again. Which makes the problem even worse. And so on.

Reducing the number of releases, increasing the overhead of releasing is the perfect way to demoralise and ultimately kill any Agile team. Why should we define short iterations and releases, if it takes so long to get something in production? Why should we collaborate tightly with customers if the software is outdated by the time it gets into the hands of users? Why should we focus on business value if potentially valuable features gather dust in an endless release process? We might as well switch to waterfall.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The first step is to regain the trust of the operational teams: release on time, deliver great quality code, involve operational teams in planning and retrospectives, treat members of operational teams (who are often involved in many projects) as members of your team: listen to them and optimise the whole value stream.

Once we’ve established trust and created one team, we can start to talk about improving and going faster.

Operational Excellence AND Customer Intimacy, but not at once

In the previous blog entry, we saw how one company resolved the conflict between operational excellence and customer intimacy. They found a way to have both. But we didn’t implement both at the same time.

We first went for Operational Excellence. First we standardised, made things reliable, made work repeatable, not only in production but also in IT. The existing product definitions were inconsistent and complex. This made our code complex because we had to treat every product as a special case. Over a period of about one year all the product definitions and the code were refactored to new standardised forms. All of this happened while the system was in production and new features were released every two months. We got very good at refactoring and migrating without disrupting because we did it so often, in small steps.

A similar ‘refactoring’ happened on the production floor. Product line by product line was tackled: work cells clearly labeled, clear flow lines from input to output established, work in process limited… When I first went to see the production floor I nearly got lost between the piles of work in process and it was hard to see what was going on. After the changes, the area looked a lot more spacious and it was clear at a glance what was going on.

Once we had the production and development system under control, we started to think about customisation and getting more intimate with our customers.

Effectiveness AND Alignment, but not at once

This reminded of Alan Kelly’s blog entry about the “Alignment Trap“. In summary: we want our IT organisations to be effective (do things right) and aligned with business objectives (do the right things). Unfortunately, most organisations do neither.

If we want an organisation that does the right things and does them right, what strategy should we follow? Based on a study, Alan conjectures that it’s best to focus on effectiveness first, alignment second. First learn to do things right, then do the right things.

Managed and Agile, but not at once

I encounter a similar situation in many coaching and consulting engagements. Organisations want IT teams that are reliable, predictable and can be trusted to deliver as promised. And they also want them to be agile, deliver faster and respond to change. Lean and Agile can get you there.

What’s the first step? Usually, we need to bring things under control, clear away the clutter, reduce chaos, limit task switching, limit work in process and make things visible. This often involves “anti-agile” or “anti-lean” measures such as batching support, analysis and design work to avoid task switching and installing strict change management and issue prioritising to keep focus. I always get lots of complaints and get accused of “not being agile” from people who are used to the chaos and suddenly find that the team no longer asks “How High?” when they yell “JUMP!” Those who stop jumping find that they get a lot more done and that the results are better. They are less stressed.

Once we have the process under control, we can start improving the flow.We know how to do things, we can start to go a bit faster, in smaller steps; we can disrupt the stability to improve a bit. And then we find a new stability and so on.

Heijunka

Heijunka is one of the often forgotten Toyota Way principles. It means “levelling the load”, working at a steady, regular, sustained and sustainable pace. It means planning the work so that there’s a good balance between flow and the load on people and machines.

Large companies who impose just-in-time deliveries to their suppliers without levelling their orders abuse their suppliers. Teams who randomly request clarifications for stories burn out their Product Owner. Teams who push out releases faster than their customers and users can accept them throw away value.

Heijunka means making and keeping work humane.

Which small step can you take to make your work more humane?

Decisions by consensus

One of the Toyota Way principles is « Nemawashi », take decisions by consensus.

Building consensus is a slow process, but it’s necessary to get everybody on board before taking a decision. Otherwise, the implementation will be delayed and (unconsciously) sabotaged by those who didn’t agree or weren’t involved.

It’s not just about building support for your ideas. The consensus-building process solicits ideas and review from everyone involved so that the final idea is usually a lot stronger than the original.

But there’s one big misunderstanding about consensus.

Consensus doesn’t require Compromise

It’s tempting to dilute our idea to reach consensus, ensure that everyone gets a bit of what they want, so that they’ll agree to go along. It’s tempting to dilute our idea to reach consensus, ensure that everyone gets a bit of what they want, so that they’ll agree to go along.

It doesn’t have to be this way. In “Extreme Toyota” the authors show how Toyota embraces conflicts and doesn’t settle for compromises. They identify six contradictions that are central to Toyota’s way of working:

- Moving gradually and taking big leaps

- Cultivating frugality while spending huge sums

- Operating efficiently as well as redundantly

- Cultivating stability and a paranoid mindset

- Respecting bureaucratic hierarchy and allowing freedom to dissent

- Maintaining simplified and complex communication

“This AND that” sounds better than “This OVER that”… I want to have my cake and eat it too 😉

Enter the business consultants

A few years ago I worked on a project that automated the whole value stream of a business unit. The main challenge was that the different departments had conflicting needs. No surprise there.

One of the conflicts was between the production department that did the work on customer demand and the sales department that sold contracts for doing the work to the customer . The production department needed standardised products with little variation so that they could work efficiently, predictably and hit their Service Level Agreements; the sales team needed customised products so that they could tailor their offering precisely to what the customer needed.

This is a classical conflict. The business consultants on the project called this “Operational Excellence” versus “Customer Intimacy“. And the consultants said we had to choose. It’s one or the other, you can’t have both. It’s like Henry Ford’s saying: “You can have any color car, as long as that color is black.”

Examining the conflict

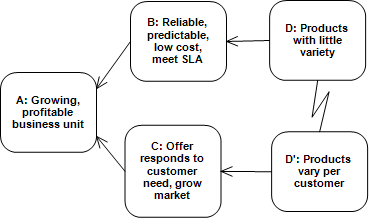

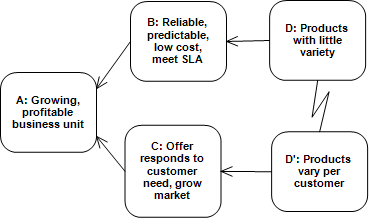

It’s clear, you can’t have both standardised and customised at the same time. There’s a clear conflict. But we have a tool to deal with conflicts: the Conflict Resolution Diagram. Let’s apply the tool:

The diagram says:

- To have a growing, profitable business unit (A) we need to sell what the customer needs (C) and deliver it reliably and cheaply (B).

- To produce reliably, predictably at low cost and to hit the Service Level Agreements (B) we need products with little variety (D).

- To create an offer that responds to the customer’s need and to grow our market (C) we need to vary our products per customer (D’).

- Conflict: we can’t have little variation (D) and a lot of variation (D’) at the same time, but we need both.

Questioning assumptions

We deal with the conflict by questioning the underlying assumptions. Can we find fault with our logic? Bill Dettmer recommends to restate the relationships in “extreme wording”. For example:

- There’s absolutely no way to have both low and high variability at the same time! Well, duh!

- The only way to be profitable and reliable is to have low variability! Well, it was hard to fault this reasoning as this company operated on large volumes with low margins and tight competition.

- Customers always need special cases! Not always, but customers were no longer satisfied with one-size-fits-all offers. If this company couldn’t offer customised products, the competitors would be more than willing to get a new customer.

- We could have low variability and yet vary per customer if only we didn’t have so many customers! Going niche wasn’t an option for economical and legal reasons.

We looked at it every way possible and couldn’t find a fault with the reasoning until…

Finally, some clarity

The Logical Thinking Processes have a set of “Legitimate Reservations”, a set of critical questions we should ask. The first one is simply called “Clarity“: is the meaning of every word and sentence clear to everybody?

Now, we had already noticed that the different departments seemed to have different definitions for the same word. There were even differences in the way they described the different products to us. Were we talking about the same thing?

The breakthrough came when we asked “What do you mean by ‘Product’?” A product for the Production department wasn’t the same thing as a product for the Sales department. And the accounting & finance department had another definition of product. But… That’s not a bug; it’s a feature: if a Production-Product is different from a Sales-Product, can we have Production-Products with low variation and Sales-Products with high variation?

After a lot more work we came up with a way to standardise Production-Products on a small set of “building blocks” and let Sales create Sales-Products by mixing and matching the building blocks according to customer need. Then we mapped Production-Products onto Accounting-Products. And everybody got what they wanted: Operational Excellence AND Customer Intimacy.

Embrace conflict

We didn’t settle for a compromise, but spent the time to really think through our conflicts and come up with a solution that satisfied all needs. A conflict can be an opportunity to come up with an innovative solution.

You don’t have to settle for compromises if you think about it.

Picture of Bonsai by A. Marques. Thank you.

|